:focal(1276x1057:1277x1058)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/68/ff/68ffe19a-9acb-430d-8c67-e8d2f2ee4aec/carol.jpg)

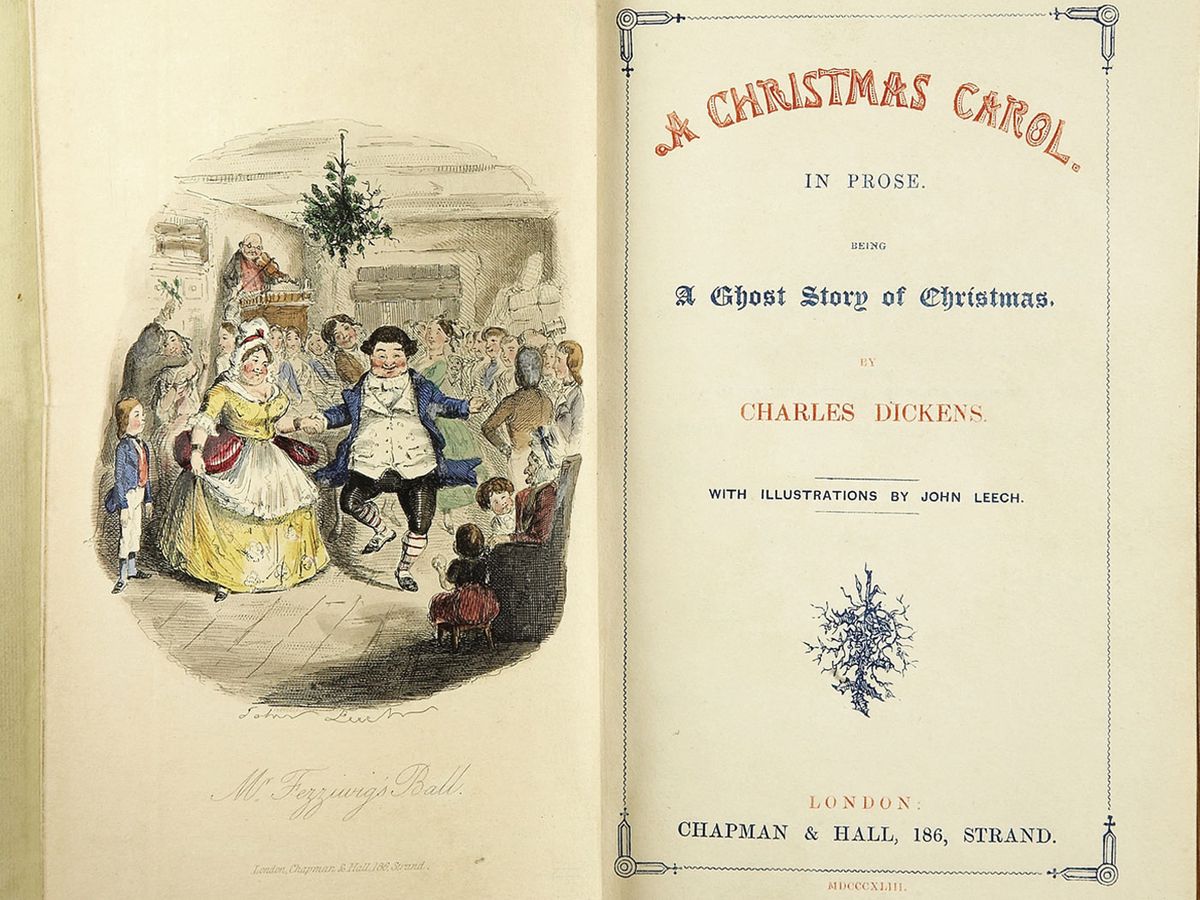

The title page of the first edition of Charles Dickens’ A Christmas carol

Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

In the foreword to his novella A Christmas carolCharles Dickens wrote that he “made an effort[ed] in this haunting little book to awaken the spirit of an idea” for his readers. “May it haunt their homes pleasantly,” he wished.

For generations, Dickens’ most iconic characters and images visit readers every holiday season, just like the curmudgeonly Ebenezer Scrooge is haunted by the ghosts of Christmas Past, Present and Yet to Come in the book.

But modern readers may not realize the extent to which their other associations with Christmas, from turkeys to charitable giving, were reinforced by Dickens’ novella, published on this day in 1843.

In the mid-19th century, Britain was in the midst of an identity crisis. The Industrial Revolution reshaped the country’s urban spaces, economic hierarchies, and society. The ‘tangible brown sky’ and beggars in the narrow, dingy streets of Dickens describes the first pages of the book contained only the most material consequences of industrialization in London.

An illustration of the ghost of Jacob Marley from the first edition of A Christmas carol/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/2c/0d/2c0dc340-4352-4899-b835-6c7b1f5c5f6c/marleys_ghost_-_a_christmas_carol_1843_opposite_25_-_bl.jpg)

By the end of the story, the formerly “gloomy” and “gloomy” Scrooge, as his nephew describes him at the beginning of the book, has been so transformed that “some people laughed when they saw the change in him.” But Scrooge makes them laugh as he cheerfully delivers a Christmas turkey for Tiny Tim’s impoverished family. “His own heart laughed,” Dickens wrote, “and that was enough for him.”

However, Scrooge’s transformation is not just a personal one. Dickens baked his social gospel deep into the story. If Scrooge’s attitude that the needy had to die to reduce “overpopulation” reflected: common vision of the day, his “feeling of penance and sorrow” upon hearing his words repeated back to him later in the story should have equally broad application, Dickens suggested.

In Callow’s words, Dickens “made Christmas the crossroads of the entire life of society, where a tremendous effort of goodwill, generosity, and integration could be harnessed to heal the running wound at the heart of the world in which he lived.” ”

Victorian society clearly had an appetite for Dickens’ warm-hearted wisdom. A Christmas carol was a blast successthe first edition of 6,000 copies sold out on Christmas Eve. It has never out of print since then.

An 1858 Harper’s Weekly illustration of a Christmas tree/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/cf/02/cf025a8f-04da-41a4-8ae3-c149127ca8ca/the_christmas_tree_harpers_weekly_vol_ii_met_dp875136.jpg)

Community and tradition were also threatened, driven apart by great economic inequality. When Scrooge’s cousin blows in from the cold with a cheerful “Merry Christmas, Uncle! God save you!” the stingy moneylender responds with his catchphrase: “Bah! Humbug!”

“It was a nervous time,” wrote literary scholar John Sutherland, and this Scrooge-like hostility to celebration and cheer was not uncommon.

Dickens himself found himself in financial difficulties in the autumn of 1843, having spent too much on a tour of America last year. He was also acutely affected by one parliamentary report from 1842 which described the plight of working-class children in British factories and mines.

When Christmas reached “unprecedented popularity” in Britain, inspired by the adoption of German festive traditions such as the Tannenbaum tree popularized by German born Prince AlbertDickens realized that a story of gaiety and charity could address both his financial problems and his moral doubts about Victorian society. wrote Simon Callow enters Dickens’ Christmas: a Victorian celebration.

Starting in October 1843, Dickens wrote the story in just a few minutes six weeksspent the days writing and the nights wandering the dark streets of London, gathering material and sentiment for his good-natured novella.

“A Christmas carol is above all about change and the possibility of change,” Callow explains. Dickens understood that Victorian society wanted to feel better, recapture the familiar feelings of a bygone era and make the joys of domestic life more recent, even as industrialization strained families. The bleak conditions didn’t have to last forever.

Leave a Reply