Just over a mile south of Northside Scrap Metals, a family-owned business that recycles “copper, brass, aluminum, cans, wire or any other junk metal,” stands the Andy Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, dedicated to one of the most influential American artists of the 20th century. Owner George Warhola took over the operation of the salvage operation from his father Paul, Andy’s brother, in 1986. “I came from nowhere,” Warhol would say when asked about his origins. The ethnic “a” at the end of his Ruthenian name disappeared when he moved to New York in 1949 to work in advertising. Yet he came from somewhere, and although he was ambivalent about Pittsburgh in life, the city adopted him and celebrated him as a favorite son in death. Ultimately, Warhol was a product of working-class, industrial, immigrant Pittsburgh, as Northside Scrap Metals should point out. Just like his cousin – who was in it job interviews fondly remembers his visit to his uncle in Manhattan; Warhol collected scrap metal and reused it. After all, the various studios where he produced his work, from East 47th to East 33rd, were always called ‘The Factory’.

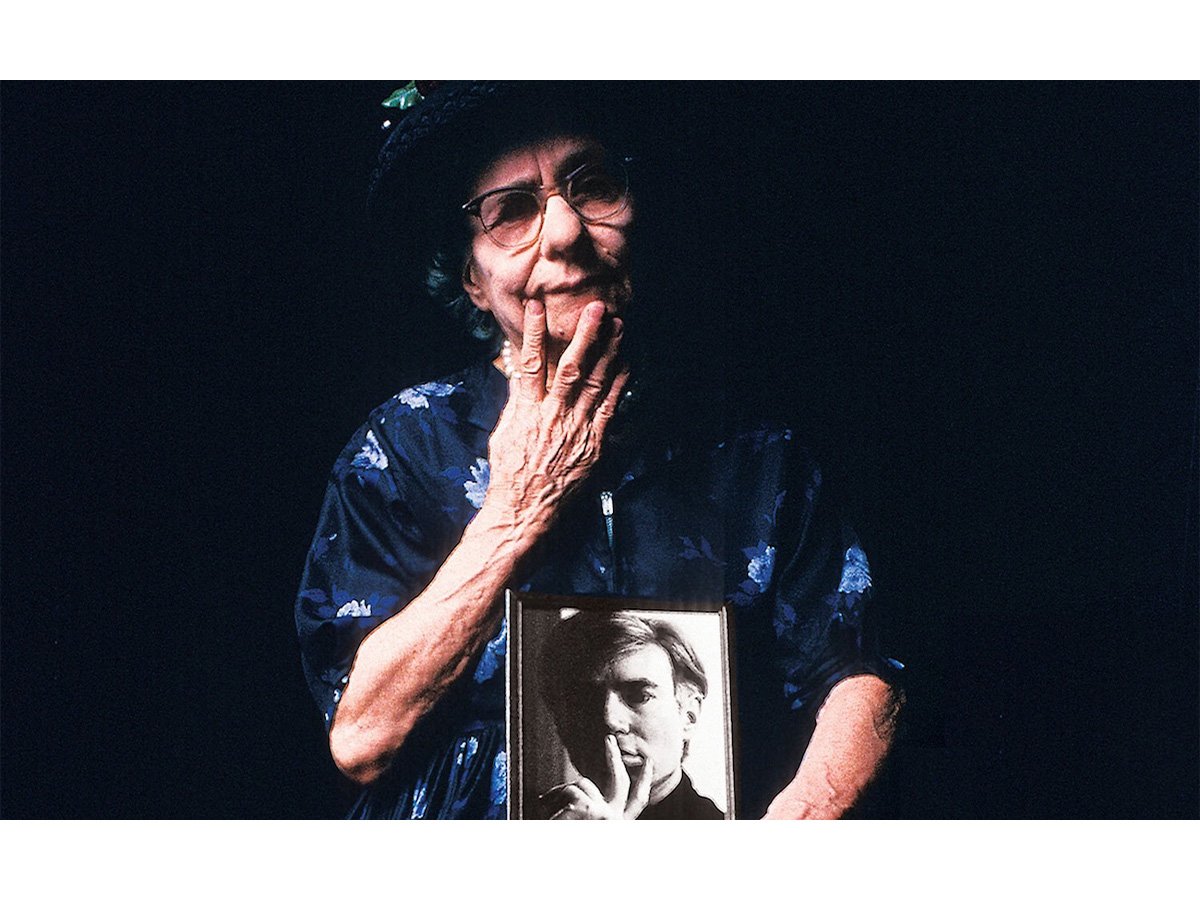

Warhol then literally took Pittsburgh with him when it came to his mother Julia, a devout Byzantine Rite Catholic and widow of a miner, biography in the book by scholar Elaine Rusinko. Andy Warhol’s mother: the woman behind the artist (2024). Julia Warhola, the petite, black-clad woman born in the Austro-Hungarian Empire who spoke primarily Rusyn, was a recognizable working-class Pittsburgher in the mid-20th century, the tough immigrant mother who supported her husband and children. And when her son Andy moved to New York City, she went with him.

That Julia lived with Andy for twenty years in a scene that included Candy Darling and Lou Reed, Edie Sedgewick and Ultra Violet cannot be so easily dismissed. Rusinko describes “the innate artistic sense that emerged from her Carpatho-Rusyn cultural background and illuminated her life in the mountains of Eastern Europe, the slums of Pittsburgh and the tumult of New York City.” As an associate professor of Russian language and literature at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County, Rusinko offers a necessary corrective to a generation of biographers who are “at best baffled by Warhol’s mother, and at worst derisive.” The first scholar with an in-depth knowledge of Carpatho-Rusyn culture to write about Warhol, Rusinko’s compelling book will undoubtedly prove to be the definitive study of Julia’s profound influence on her son.

Rusinko explains how Warhol emerged from a “potentially harrowing life” in which Eastern European immigrants were derided as “mill hunkies” and men like his father would die in industrial accidents, but that his rise into a glamorous world of “fame and unimaginable fortune ‘ was in large part due to his mother, who ‘defied the limits imposed on her by poverty, hardship and illness’. Without Julia’s emotional support, it is difficult to imagine what would have become of her eccentric and strange son who grew up on the rough streets of South Oakland. Julia’s work cleaning houses allowed Warhol to take childhood art classes at the Carnegie Museum of Art and attend the College of Fine Arts at the Carnegie Institute of Technology, now Carnegie Mellon University.

But support wasn’t the only thing she gave her son; Julia Warhola also provided artistic inspiration. As Rusinko makes clear, Julia was a woman of tireless talent and creativity. Julia, calligrapher, embroiderer and illustrator, created avant-garde, ready-made sculptures from that most Warholian commodity: the can. After trading the ethnic icons of Saint John Chrysostom Church in Pittsburgh’s Four Mile Run neighborhood for the Anglophile Gothic of Saint Vincent Ferrer on the Upper East Side, where Julia attended daily Mass with her son (both crossed paths) the Byzantine way), mother brought her own sensitivity to New York.

Appears in her son’s experimental films, especially 1966 Mrs. Warhol, is part of what made art critics like Gilda Williams tick to describe Julia Warhola, the artist’s “strange, foreign mother,” was dismissed as a “woman who never adapted to the American way of life.” Rusinko eschews such misconceptions and instead interprets Andy’s mother as a collaborator; she writes that “influence [was] unconsciously transmitted from Julia to Andy… evident in his temperament and worldview, a down-to-earth practicality and superstitious mysticism.”

Re-centering the woman who was too often subtracted from her son’s biography, Andy Warhol’s mother refutes the myth of Warhol sui generis. This book follows on from the excellent 2022 by Maxwell King and Louise Lippincott American Workman: The Life and Art of John Kane, about the self-taught Scottish immigrant painter of the early 20th century, as a superlative work of working-class art history in Pittsburgh, published by the University of Pittsburgh’s own Press, which is quickly becoming the leading publisher in the field.

Classism often obscures the fertile proletarian soil from which much American modernist art emerged, but studies like Rusinko’s remind us of the ethnic and working-class origins of these artists. For Julia Warhola was not only a passive actress in Andy’s films, but also the calligrapher and co-illustrator for books like the charming 25 cats named Sam and one blue kitty And Holy cats (1954), who combined her love for angels and felines. As a solo artist, she won a Certificate of Merit from the American Institute for Graphic Arts in recognition of the 1957 album cover design for the groundbreaking experimental record The story of Moondog. And yet the attribution of these joint works? “Andy Warhol’s mother.” Rusinko’s book reminds us that she, Julia, was much more than that.

Andy Warhol’s mother: the woman behind the artist (2024) by Elaine Rusinko is published by the University of Pittsburgh Press and is available online and through independent booksellers.

Leave a Reply