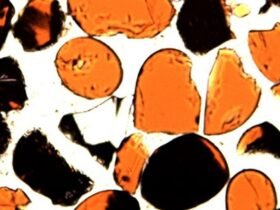

Minions are characters in films produced by Universal Pictures

Cinematic/Alamy

Disney and Universal have filed a lawsuit against AI image generator Midjourney alleging mass copyright infringement that enables users to create images that “blatantly incorporate and copy Disney’s and Universal’s famous characters”. The action could be a major turning point in the legal battles over AI copyright infringement being negotiated by book publishers, news agencies and other content creators.

Midjourney’s tool, which creates images from text prompts, has 20 million users on its Discord server, where users type their inputs.

In the lawsuit, the two movie-making giants share examples in which Midjourney is able to create images that uncannily resemble characters each company owns the rights to, such as the Minions, controlled by Universal, or the Lion King, owned by Disney. The companies allege those outputs could only be the result of Midjourney training its AI on their copyrighted material. They also say Midjourney “ignored” their attempts to remediate the issue prior to taking legal action.

In the complaint, the companies say “Midjourney is the quintessential copyright free-rider and a bottomless pit of plagiarism.” Midjourney did not immediately respond to New Scientist‘s request for comment.

The lawsuit has been welcomed by Ed Newton-Rex at Fairly Trained, a non-profit organisation that promotes fairer training practices for AI companies. “This is a great day for creators around the world,” he says. “Governments have shown worrying signs they might bend to big tech’s intense lobbying by legalising IP theft – Disney weighing in makes this that much less likely.”

Newton-Rex claims Midjourney engineers once told him their actions were justified because art is “ossified”. “Thankfully, this ludicrous defence wouldn’t stand up in court,” he says.

Legal experts are equally forthright about Midjourney’s likelihood of success defending the case. “It’s Disney, so Midjourney are fucked, pardon my French,” says Andres Guadamuz at the University of Sussex in the UK.

Guadamuz points out that Disney’s general approach to protecting its intellectual property – rarely, but firmly when it does – highlights the importance of its intervention. The movie companies acted months after other organisations, including news publishers, pursued AI firms over the alleged use of their proprietary creations. Many of those cases have settled after licensing agreements were reached between the AI companies and copyright holders.

“Media conglomerates are more interested in infringing outputs. The models are getting so much better that it’s now very easy to produce pretty much any character you can imagine,” says Guadamuz. He thinks Disney waited because “unlike publishers, they’re not looking for licensing agreements to survive”.

The involvement of two titans of the creative industry is revealing in itself and marks a watershed moment for AI and copyright, Guadamuz reckons. “The fact that they’re going after Midjourney is telling,” he says. The company is a minnow compared to larger AI firms because it only specialises in image generation. “This is a message to the larger players to get their act together and start implementing stronger filters, or they’ll be next.”

Many large AI companies provide image generation tools within their chatbots, though they tend to more strictly police users’ ability to create images incorporating copyrighted characters through blunt guardrails preventing them from even trying.

The less likely alternative is that Disney, which made $91 billion in revenue last year, is seeking to get money from Midjourney. “This could also be a message to come to the table and start negotiating. AI isn’t going away, so Disney may be setting this as a marker that they’re open for business,” says Guadamuz.

Topics:

Leave a Reply