It may come down to a coin toss as to whether the Milky Way collides with the Andromeda Galaxy within 10 billion years.

While scientists have previously reported that a convergence was certain, an analysis of the latest data suggests the odds are only about 50 percent, researchers report June 2 in Nature Astronomy. The Milky Way’s largest satellite system — the Large Magellanic Cloud — may be our galaxy’s saving grace, the study shows.

We summarize the week’s scientific breakthroughs every Thursday.

“What stands out is the role of the Large Magellanic Cloud,” says astrophysicist Elena D’Onghia of the University of Wisconsin-Madison. “It’s not just a minor satellite, but it’s a major player.”

A little over a hundred years ago, astronomer Vesto Slipher first observed that Andromeda, the closest major galaxy, appeared to be approaching the Milky Way. A century later, researchers used NASA’s Hubble telescope to measure Andromeda’s movement across the sky, leading them to report in 2012 that it was bound for a direct strike with the Milky Way, and subsequent studies confirmed the convergence. “The idea of the collision has been accepted for a long time,” D’Onghia says.

But those earlier studies had not fully considered the influences of the Large Magellanic Cloud, says astrophysicist Till Sawala of the University of Helsinki in Finland. It’s the fourth largest galaxy in the Local Group, a gravitationally bound neighborhood of galaxies that’s dominated by the Milky Way and Andromeda. The Large Magellanic Cloud may have been left out because the data available at the time led researchers to believe it was relatively insignificant, Sawala says. But over the last decade, observations have revealed that the galaxy is more massive than had previously been proposed.

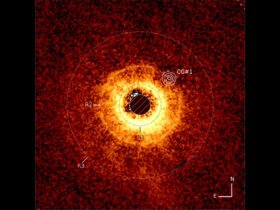

Curious as to how the latest and most accurate data from Hubble and the European Space Agency’s Gaia telescope might shift the odds of a galactic smashup, Sawala and colleagues simulated the movements of the Milky Way, Andromeda, the Large Magellanic Cloud and Messier 33 — the Local Group’s third largest galaxy — over 10 billion years. The team performed roughly 100,000 simulation runs to test every possibility across the full range of uncertainty in the data.

With the new data, simulations of just the Milky Way and Andromeda produced collisions a little less than half the time, they found, and adding in Messier 33 increased the collision odds to about 66 percent. But when the team incorporated the Large Magellanic Cloud, the odds dropped to just over 50 percent.

The gravity of the Large Magellanic Cloud appears to introduce some sideways momentum to the Milky Way’s path, tugging it out of Andromeda’s way in roughly half of the simulation runs, Sawala says. But the save may be a thankless one, as the results suggest the Milky Way is certain to collide with and engulf the much smaller Large Magellanic Cloud in about 2 billion years.

The results “show that the situation is more uncertain than previously thought,” says D’Onghia, who was not involved in the work.

But not all agree that the odds are so even. While it’s good that the study considers these other galaxies, “I can’t see how they would actually change the course of the merger,” says astrophysicist Sangmo Tony Sohn of the Space Telescope Science Institute in Baltimore, coauthor of the 2012 study that predicted the head-on convergence. Based on his and his colleagues’ interpretation of the data, they believe the combined mass of the Milky Way and Andromeda is greater than what’s assumed in the new paper, which would make them more prone to coalesce. “I’m someone still who actually believes that there’s a higher chance of the two galaxies merging,” he says.

Consensus may be reached in the next decade, both Sawala and Sohn say, as better instruments and methodologies and more observations become available. Part of that will involve refining estimates of how much dark matter each galaxy possesses, as the invisible substance is thought to dominate their masses.

If the collision does ever occur, it may not matter much to Earth. The sun is expected to swallow up the inner planets and collapse into a white dwarf in about 8 billion years, so “there’s a fairly good probability that even if that merger happens, it will happen after the solar system doesn’t exist anymore,” Sawala says.

Sponsor Message

“It has no relevance for my own life or the life of my children,” he says. But “for some reason, I prefer that the Milky Way continues to exist.”

Source link

Leave a Reply