We are living through a period of unprecedented species extinction due to human-induced changes to the planet’s ecosystems. This is not the first time human activities radically changed relationships between land and life.

Illustrated by a famous photograph of remains, the extermination of bison from the North American West in the 19th century is one key example of catastrophic species loss.

As a visual studies researcher, I use photographs to analyze the impacts of colonization on human and non-human lives.

Images of bison bones provide a window into the cultural and ecological relations that tie animal and human lives together. Through photographs, we can also think about bison extermination as part of a history of relationships.

An iconic image

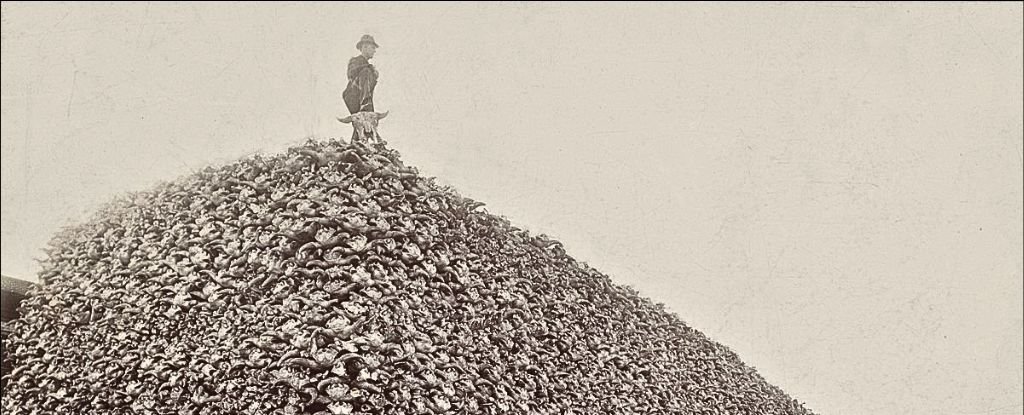

The most famous photograph of bison extermination is a grisly image of a mountain of bison skulls. It was taken outside of Michigan Carbon Works in Rougeville, Mich., in 1892.

This photo from 1892 shows two men with an enormous pile of American bison (buffalo) skulls.

Originally numbering 30-60 million, commercial hunting and government campaigns aimed at destroying the Indian way of life ultimately reduced the total bison population to <1,000. pic.twitter.com/txFO2BCc3U

— Dr. Robert Rohde (@RARohde) June 26, 2023

At the close of the 18th century, there were between 30 and 60 million bison on the continent. By the time of this photograph, that population was reduced to only 456 wild bison.

Increased colonization of the West led to the large-scale slaughter of bison. The arrival of white settler hunters with their weapons, as well as growing market demand for hides and bones, intensified the killing. Most herds were exterminated between 1850 and the late 1870s.

The photograph shows the massive scale of this destruction. A man-made mountain emerging from the image’s grassy foreground, the pile of bones as appears part of the landscape. The image can be read as an example of what Canadian photographer Edward Burtynsky has called “manufactured landscapes.”

What was taken from prairie land to make this manufactured landscape in Michigan?

The Rougeville photograph is often used to illustrate the scale of bison extermination. It appears in conservation publications, magazines, films and recent protest memes. The photograph has become an icon of this animal’s slaughter.

But this photograph is more than just a symbol of human-caused destruction and hubris. Analyzing the image with multiple lenses illustrates a history of relationships.

The mound of skulls also indicates the abundance of bison life. But what was life on the Prairies like before bison extermination? What relationships did bison have before their deaths?

Human-bison relationships

We know that Indigenous Nations and bison herds were closely linked. The vast number of bison herds shaped the lives of Indigenous Nations by facilitating the formations of large, politically and socially complex communities across the Prairies.

Many Indigenous scholars demonstrate the interrelation of Plains Indigenous Nations and bison herds, sometimes referred to as buffalo.

For example, Cree political scientist Keira Ladner studied the non-hierarchical organization of Blackfoot communities and practices of collaborative decision-making. These community practices are rooted in close relationships to bison herds, which work as non-coercive collectives in which no single animal dominates.

Similarly, the Buffalo Treaty, an Indigenous-led effort to reintroduce wild bison first signed in 2014, describes the buffalo as a relative of Plains Indigenous peoples.

The treaty states: “Buffalo is part of us and we are part of buffalo culturally, materially and spiritually.”

frameborder=”0″ allow=”accelerometer; autoplay; clipboard-write; encrypted-media; gyroscope; picture-in-picture; web-share” referrerpolicy=”strict-origin-when-cross-origin” allowfullscreen>

Cree scholar and filmmaker Tasha Hubbard has documented stories about bison extermination from many Plains Indigenous Nations. These stories mourn the trauma of losing bison – a non-human community many Indigenous Nations see as relations. Extermination radically undermined possibilities of life for Indigenous and bison communities. Hubbard argues that bison extermination was a form of genocide.

Through the lens of interrelationship, the photograph takes on additional meaning. As Dakota scholar Kim TallBear reminds us: “Indigenous peoples have never forgotten that non-humans are agential beings engaged in social relations that profoundly shape human lives.”

The pile of skulls is not only symbolic of the destruction of an ecosystem. It is also a symbol of the loss of relations.

Multi-species relationships

Bison made the Prairies hospitable for many other communities. Each skull represents one 600-kilogram animal — bison are the largest land mammals in North America.

Bison are not just massive in size, they are also a keystone species in the West, meaning they have a dramatic influence on an ecosystem. If one of these species disappears, no other species can fill its ecological role, and the whole ecosystem changes as a result.

The skulls in the photograph do not just represent the loss of bison, but the disruption of an entire ecosystem. Each bison killed meant the end of grazing, wallowing and migrating practices that make the land hospitable for other species.

For example, hundreds of species of insects live in bison dung, providing food for birds, turtles and bats.

When bison roll in dirt, they create depressions called wallows, which fill with spring rain and provide homes for tadpoles and frogs. Without the presence of bison, habitats and food for these and many other species disappear.

Colonial capitalist relationships

The bison skulls are not alone in the photograph. Two men in suits pose proudly with the skulls. Their presence signifies another aspect of human-animal relationships: commodity or market relations.

Each skull was collected from across the Prairies and shipped east by train or steamship. Once they arrived at facilities like Michigan Carbon Works, bison bones were rendered as fertilizer, glue and ash.

The bones produced commodities, like bone china, which were sold in European and North American cities. Crates – like the large one in the foreground of the image – were technologies of colonial capitalism, moving bones from prairies to factories and then finished products to market.

The photograph also represents the network of infrastructures that settler colonial agents imposed across North America. Settler infrastructure – from railways and roads to factories and markets – radically intensified the transformation of animals into commodities.

The extractive industries of colonial capitalism devastated habitat and biodiversity, as well as relationships between bison, other plant and animal species and Indigenous Nations. Similar industries are driving the large-scale extinctions happening today and predicted to continue in the near future.

Looking ahead

There are currently 31,000 wild bison living in conservation herds in North America. The species is considered “near threatened” on the International Union for Conservation of Nature Red List. This indicates that conservation efforts have improved chances for bison species survival, but protections are still needed.

These remaining animals are the descendants of those few hundred bison who survived the 19th-century extermination. With the help of conservation projects, including the Indigenous-led Buffalo Treaty and InterTribal Buffalo Council, bison continue to survive.

As a close reading of the Rougeville photograph from multiple perspectives demonstrates that the scale of bison loss is dramatic. Relationships on the Prairies were forever changed by the extermination of the species in its wild, free-ranging form.![]()

Danielle Taschereau Mamers, Postdoctoral Research Fellow, English and Cultural Studies, McMaster University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

This article was originally published by The Conversation in December 2020. We are republishing it now due to recent media coverage of the historical photo.

Leave a Reply