Communities on the Cranberry Isles, an archipelago off the coast of Maine named for its annual harvests of cranberries, have lived on the edge of marine life for generations as boat builders and fishermen, enjoying the islands’ bounty. However, since the 1920s, the number of year-round residents has steadily declined, while the number of vacationers has increased. Today, three of the five islands are completely uninhabited by permanent residents. But as Lauret Savoy writes in her book Trace: Memory, History, Race, and the American Landscape (2016), “The memory of all forms is engraved in the land.”

The late Emily Nelligan, who passed away in 2018, was one such visitor who left a mark on the islands. Although she lived in Connecticut, she spent summers on Great Cranberry Island, a two-mile-long mountain range that encloses a large bay known as the Pool, home to oysters and shellfish. Nearly all of her charcoal drawings focused on the Cranberry Islands in a kind of lifelong self-portrait. An exhibition at Alexandre Gallery, Emily Nelligan: Early Drawingsshows her works from the fifties and eighties. The almost identical compositions express mystical life forms that resemble an enchanted one Odilon Redon or disorienting Gustav Klimt. Entire compositions are covered with grass or washed out with glints of sunlight.

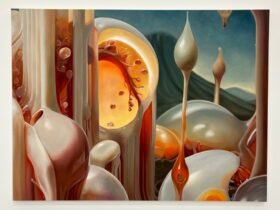

During the Paleozoic era, lava flows raised mountains. The intense pressure crystallized the heavy rock layer beneath the island’s surface. Glacial transit shed the earth, creating the bays and valleys that form Maine’s landscape. Nelligan worked in charcoal to save money, but her mastery of the medium’s grayscale tonal shifts created scenes that suggest the land’s primal beginnings. She darkens the paper without weighing it down. “September 1, 62” (1962) is depicted in the foreground by orbs shifting from rocks to bubbles in the viewer’s eye, with a mass of faint pine trees in the background. She found the ethereal in the old; her drawings swirl like metamorphic rock.

Nelligan’s works are modest in size and offer intimate windows onto the landscape. Yet they refrain from orienting the viewer. Parts of the island are crooked or abstracted. In ‘On the Road to Manset’ (1982), a black opening disappears into the sides of the drawing. The top of this void is textured with points like pine. Below, the dark cut extends into gray ribbons. Above, an interior light glows – a light that seems to carry each of her compositions. White ovals scallop into the distance. This is an island; these are clouds and water – but here they are only shadows.

The specificity of her line drawings of individual plants contrasts with the abstraction of her landscapes. “Untitled” (1975), for example, is one of a series of ink drawings of geranium plants. Leaves emerge from stems almost bursting with nodes. Although the viewer can barely distinguish one location from another in her images of land masses, the veins of these leaves are distinct enough to resemble maps.

Her triptych ‘Woods near Preble Cove’ (1982) is nothing more than tree trunks that repeat themselves along three narrow sheets of paper. The sense of place is confusing; the trees are nowhere. They grow like echoes of themselves. There is no sign of life. Yet the shadows and light pulsate. With a turn of the wind, someone could walk out of the trees. Nelligan maintains the land with the intimate repetition of a lifelong student. It’s as if, with a slight gray blush, she can filter away the millennia and reveal all the life of the place at once.

Emily Nelligan: Early Drawings continues at the Alexandre Gallery (25 East 73rd Street, Upper East Side, Manhattan, through November 16). The exhibition was organized by the gallery.

Leave a Reply