In central Florida, Ocala National Forest is dotted with more than 600 lakes and rivers. A nearby recreation center, Silver Springs, has been capitalizing on the tourism potential of these sparkling, clear bodies of water for decades, offering sandy riverside beaches and taking visitors on trips in glass-bottom boats.

Until 1968 and the passage of the Civil Rights Act, Silver Springs—similar to many other places in Florida and the South more broadly—was racially segregated and open only to white patrons. In 1949, the owners of Silver Springs opened Paradise Park a mile away as a destination “for people of color,” as the welcome sign read, who were not allowed to enter the other resort.

Paradise Park was one of three beaches in Florida open to black visitors during this time and also offered sandy beaches, glass-bottom boat rides, a petting zoo, a dance pavilion with a jukebox, performances, games and a softball field. It remained in operation until 1969, shortly after desegregation, and became a subject of fascination for photographers. Bruce Mozert (1916-2015), who documented the events in both recreation areas.

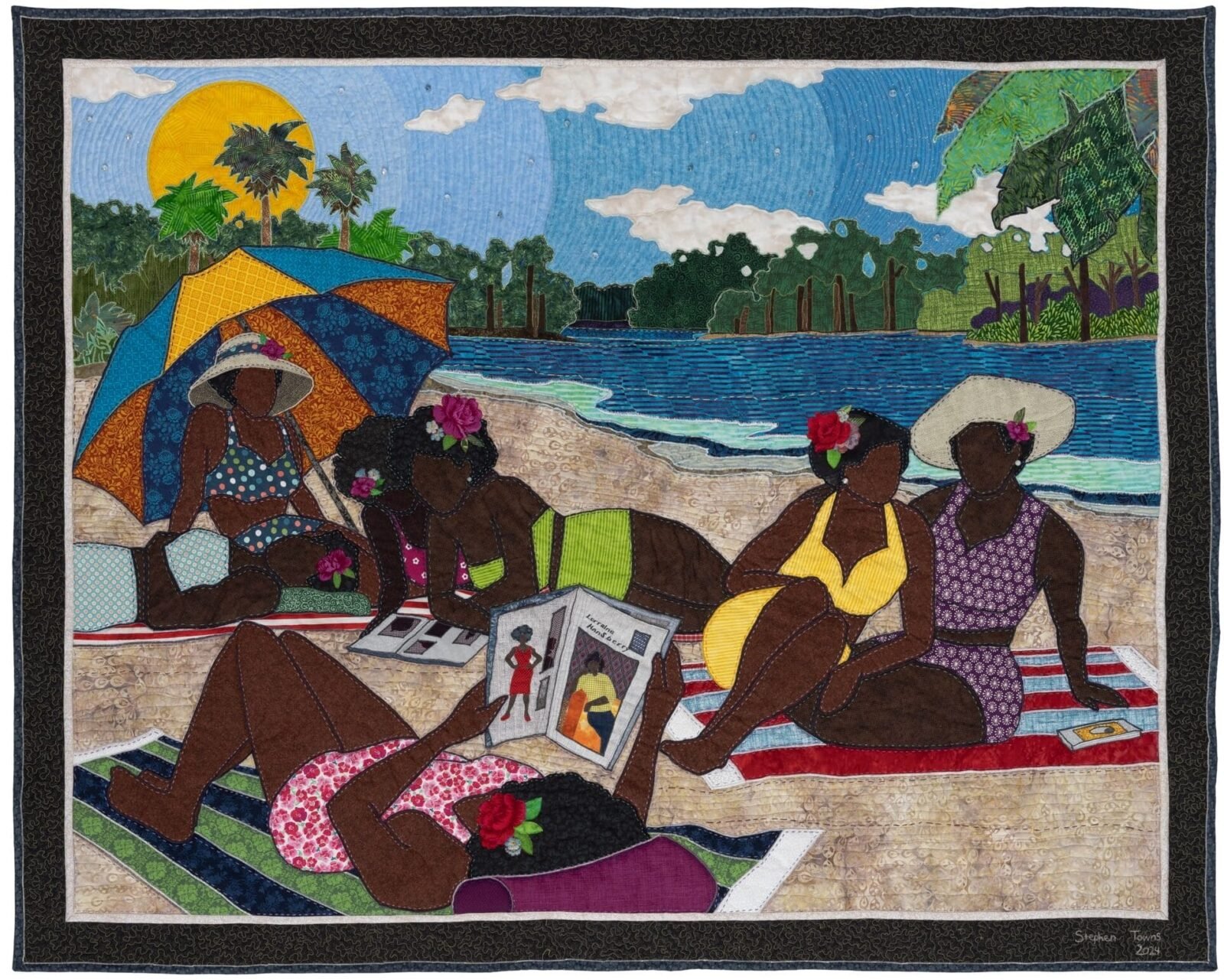

For artist Stephen TownsThe images of Mozart and the history of Paradise Park form the basis Private Paradise: a figurative exploration of black rest and recreationnow on display in the Rockwell Museum. Through paintings and quilted compositions, the artist explores how certain parks could have been places of refuge and recreation for black Americans during the Jim Crow era.

“Black people had to carve out their own spaces to find recreation and peace,” Towns says in a video accompanying the exhibit. “This show is a way to clarify that. It gives people a way to access history that isn’t as scary as other forms.”

Towns’ paintings depict groups of children swimming, sunbathing and playing on the sandy beaches. His material compositions are imagined scenes of peace and solidarity, which appear disarming and candid.

“Motown in Motion,” for example, shows a group of young people gathered on the beach, and “I Will Follow You My Dear” follows two women swimming underwater—another nod to Mozert’s work as a pioneer of underwater photography.

The figures in Towns’ paintings are more posed, taken directly from Bruce Mozert’s snapshots, and depict smiling children at play. Cities often use reflective materials, such as metal leaves, that radiate light back to the viewer, repeating a sense of brightness. “I want people to feel that warm, reflective energy when they see the show,” he says.

Discover more about Towns’ website And Instagramand if you are in New York you can see it Private paradise in Corning through Jan. 19.

Leave a Reply