After I visited Surreal at Tibor de Nagy, Jimmy Gordon’s debut exhibition in New York, I did some research to find out more about who the artist was. The press release stated, “Gordon (1947–2022) was born in Lexington, Kentucky,” his “paintings [were] created between the 1990s and the mid-2000s’, and he had an ‘alter ego, which he called La Jimberly’ and sometimes lived in that persona for weeks and months at a time. During these times he always signed his artwork Jimberly instead of Gordon.

I associate Lexington with a generation of artists who first came to attention in the 1960s and 1970s, including the Catholic monk and writer Thomas Merton, who lived at Gethsemani Abbey (near Lexington) and was a friend of Ad Reinhardt; polymath writer and translator Guy Davenport, who taught at the University of Kentucky; self-taught photographer Ralph Eugene Meatyard; photographer Guy Mendes, who, along with poets Roger Manley and Jonathan Williams, documented his road trips through the southern United States and introduced readers to a wide range of self-taught artists, local architecture and local landmarks; and environmentalist and farmer Wendell Berry.

I’ve wondered if the aura of this band of iconoclasts disappeared when many of its prominent figures died. Were there others connected to this group, however superficially, who never received recognition? Were there equally interesting groups that became overshadowed? Gordon seemed both connected to this older generation, due to his interest in surrealism combined with his fluid identity, and separated from them because his work was not as visually sophisticated as theirs. This doesn’t make his paintings any less compelling, especially those inspired by his time at a circus in Sarasota, Florida. They just need to be understood differently.

After two tours of duty during the Vietnam War, Gordon received his BFA from the University of Kentucky, where he studied with artist Henry Faulkner. Faulkner was known for his brightly colored, imaginative paintings of subjects such as a unicorn looking in the mirror and applying makeup. Tennessee Williams was his good friend and was rumored to be his lover. According to his Wikipedia page, he was a pioneer of Kentucky’s LGBTQ+ scene in the mid-20th century, sometimes dressing in drag for weeks at a time. He became a local legend in Lexington, and in the late 1940s he lived in New York with Thomas Painter and Kentucky-born Edward Melcarth, an openly gay artist who incorporated Renaissance techniques into paintings celebrating masculinity. The connection between Melcarth, Faulker, and Gordon suggests the porousness of Lexington’s society and the different, overlapping social circles in which they found themselves, as they came from very different financial and educational strata. At the same time, the radical differences in the groups’ style, subject matter and techniques are revealing.

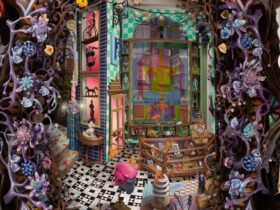

Six of the show’s fifteen paintings (all but one in a frame created by the artist) reference the circus and traveling sideshow acts. In “HERMAPHRODITE: ALIVE” (ca. 1999–2002) and “BEARDED WOMAN: ALIVE” (2002), Gordon’s fascination with fluid identity and sexuality is evident. He based his compositions on circus posters, in which the frame is incorporated. The curtains are pulled back to reveal the figure or figures in isolation. Stylistically, the artist focuses on the posture of the body, rather than the face. By including the title in the painting, he emphasizes the characters’ public identity as what isolates them from mainstream society and, as the curtains imply, defines them as a voyeuristic curiosity. With his claw-like hands and feet, the young boy in “LOBSTER BOY,” sitting in front of his jacks game, is heartbreaking to watch as his isolation feels complete and inescapable. In these paintings, very different from the whimsical works of Faulkner, Gordon found his most enduring subject.

The nine surviving paintings, for which the exhibition is probably titled, show the influence of Max Ernst and Giorgio de Chirico. What keeps them from getting distracted is Gordon’s addition of quirky or unexpected details. For example, the bust on the table in “THE LAPWING KNOWS” (undated) has pointed ears and a green-haired style that mimics a mohawk or the decoration of an Athenian war. helmet, while flying saucers are visible through what appears to be a window above a table with bizarre objects in “DYNAMITE Still Life” (2008). In these and several other works, Gordon’s vision of social reality as populated by those alienated from it is evident.

Jimmy Gordon: surreal continues at Tibor de Nagy (11 Rivington Street, Lower East Side, Manhattan) through October 12. The exhibition was organized by the gallery.

Leave a Reply