DÜSSELDORF, Germany – The first extensive research in Germany by American feminist artist and video pioneer Lynn Hershman Leeson, at the Julia Stoschek Foundation, Düsseldorf, is an exciting, yet terrifying experience. As an early adopter of video technology, the artist was one of the first to grapple with the rich potential of digital tools. The research, featuring video installations, photography and mixed media, shows the artist wielding a camera in an intimate and confessional way, using it to explore notions of authenticity and truth, and criticizing digital images themselves as a rapidly growing tool of surveillance. In that sense, the title of the show is, Are our eyes targets?is particularly apt and chilling: eyes, as the saying goes, are the windows to the soul – but in our times, baring the soul for the camera comes with a hefty price tag. The more advanced digital technology becomes, Hershman Leeson seems to warn, the more vigilant we all must be against its lurid temptations.

Upon entering the space, visitors are immediately confronted with multiple portraits: the artist’s face populates all six video channels with excerpts from Hershman Leeson’s groundbreaking video art series, The Electronic Diaries of Lynn Hershman Leeson 1984–2019 (1984–2019). Transparent glass walls divide the screens, making the images appear to interpenetrate. The visual cornucopia is a striking embodiment of how the artist saw himself: as an enigma, shattered by trauma. In imaginary fragments, aided by expressionistic, dreamlike fragments from early cinema, she talks about domestic sexual and physical abuse she suffered as a child. Heartbreaking, dark and courageous, the work powerfully breaks the taboo against speaking about such trauma outside a psychoanalyst’s office. But it’s the intimacy of the video that’s most compelling: the whispering, the close-up, the averted gaze—all reinforce a sense of diary-like, confessional connection, in a way that builds a kind of conspiracy between artist and viewer.

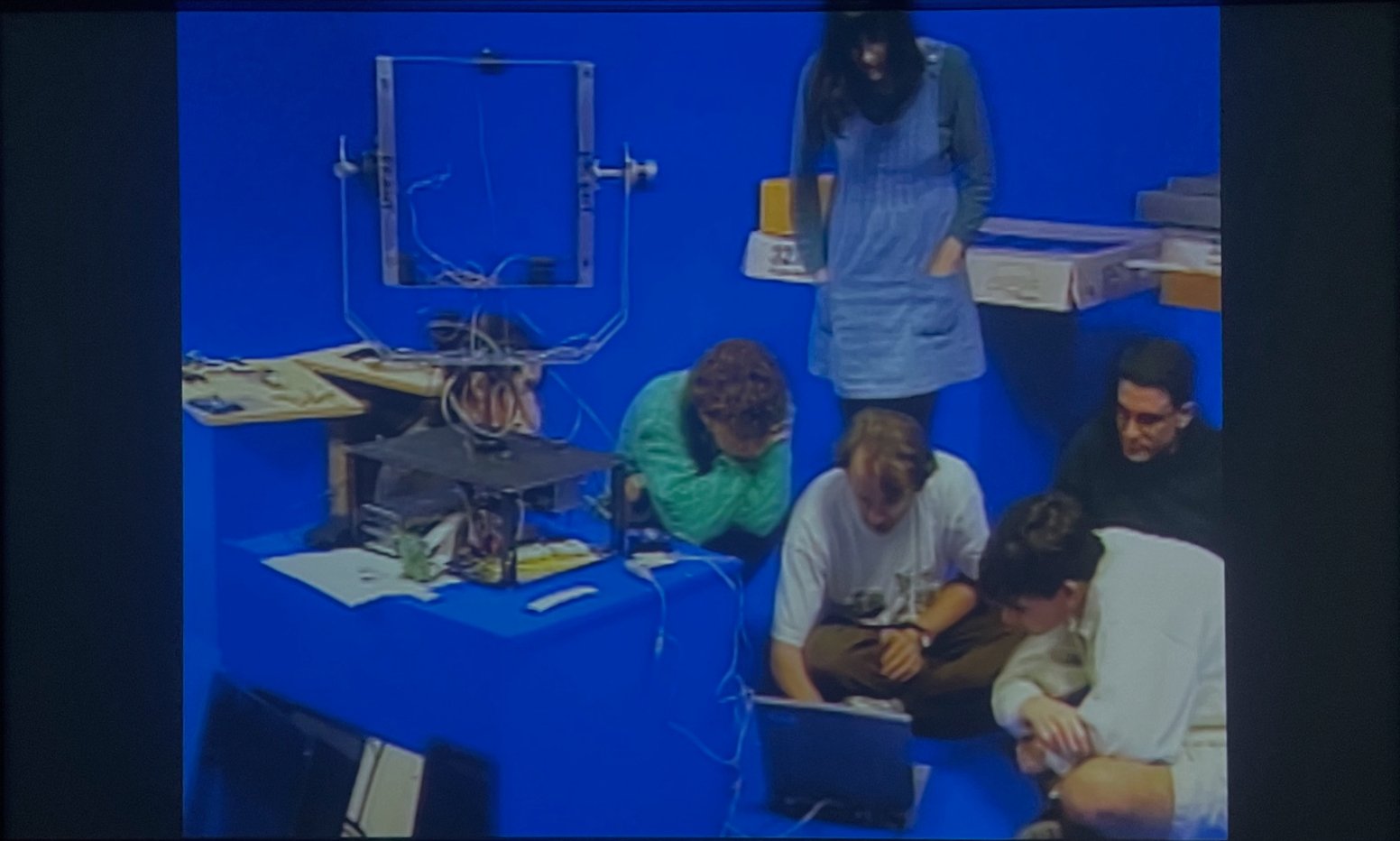

Other excerpts show Hershman Leeson’s self-described “private apocalypse”: divorce, wildly fluctuating weight, binge eating, sudden life-threatening illness. Yet there is also a sense of healing in these voiceovers, as when she recounts the experience of a sudden sense of déjà vu after the death of her abusive father, as well as descriptions of her daughter’s birth and her new marriage. Elsewhere she expands the scope of Electronic diaries to record interviews with scientists. Drawing on her own intimate relationship with video, she imagines a cyborgian future in which humans merge with technology. At first glance, this merger sounds vaguely optimistic. But by the end of the project, she is clearly ambivalent: in 2019, the final year of the series, she encoded the series’ video archive onto a DNA strand to create a durable archive (the lifespan of the genetic material is longer than that of a hard drive), but regrets the invasiveness of the same procedure.

The dark tone should come as no surprise. In the caustic “Paranoid” (1968–2022), which opens the Stoschek show, a butterfly pin wig nestled in a glass harasses visitors as they approach with words like, “You think you’re so smart,” ‘Please go away. away,” and “Look at someone else. Look at yourself.” And as early as 1994, the artist conveyed grim messages about digital dependency, aggression and intrusiveness in works like “Seduction of Cyborg,” also shot at Stoschek, which follows a young woman who gets sucked into her computer screen. Another work, “CybeRoberta” (1996), consisting of a seemingly ordinary doll sitting in a glass display case, allows viewers to access a designated website via a QR code displayed on the wall and then adjust the position of the digital screen to change from “Roberta”. eye to see real-time images of themselves in the gallery. Needless to say, having myself so thoroughly watched by a seemingly benign toy was morbidly compelling, but also truly disturbing.

A more recent video, “Shadow Stalker” (2018–21) confronts the controversial surveillance software Predpolthat uses data analysis to predict crime. In it, a revolutionary black woman played by Tessa Thompson denounces a culture of paranoia created by racial data-enabled policing. In portraying the escalation of techno-social dystopias, Hershman Leeson reminds viewers that digital technologies and the images they help capture and disseminate have never been neutral receptacles of personal truths, but have instead always been political battlegrounds.

Lynn Hershman Leeson: Are our eyes a target? continues until February 2, 2025 at the Julia Stoschek Foundation (Schanzenstraße 54, Düsseldorf, Germany). The exhibition was organized by Lisa Long and Line Ajan.

Leave a Reply