What does Intel’s Pentium computer chip have in common with Navajo textiles? More than you might think.

For artist Marilou Schultzthe ancestral practice of weaving merges with an unexpected contemporary source of inspiration. By merging analog loom methods with the patterns found in the cores of computer processors, Schultz interweaves the history of the Navajo people with modern technology.

In the late 17th century, Spanish settlers introduced a breed of sheep called the Iberian Churro to the American Southwest. The Diné, also known as Navajo, who had lived in the Four Corners region for hundreds of years, embraced pastoralism and wool production, eventually developing a unique breed that is still managed today, the Navajo-Churro.

In addition to an aptitude for sheep breeding, Diné weaving traditions flourished. Anthropologists suspect that the craft was adopted from the neighboring Puebloans sometime in the 12th or 13th century. As time went on, Navajo styles and techniques evolved, becoming popular first among the Plains Indian tribes and then, in the 19th century, with Europeans and non-native tourists who sought out blankets and rugs for their remarkable craftsmanship and geometric patterns.

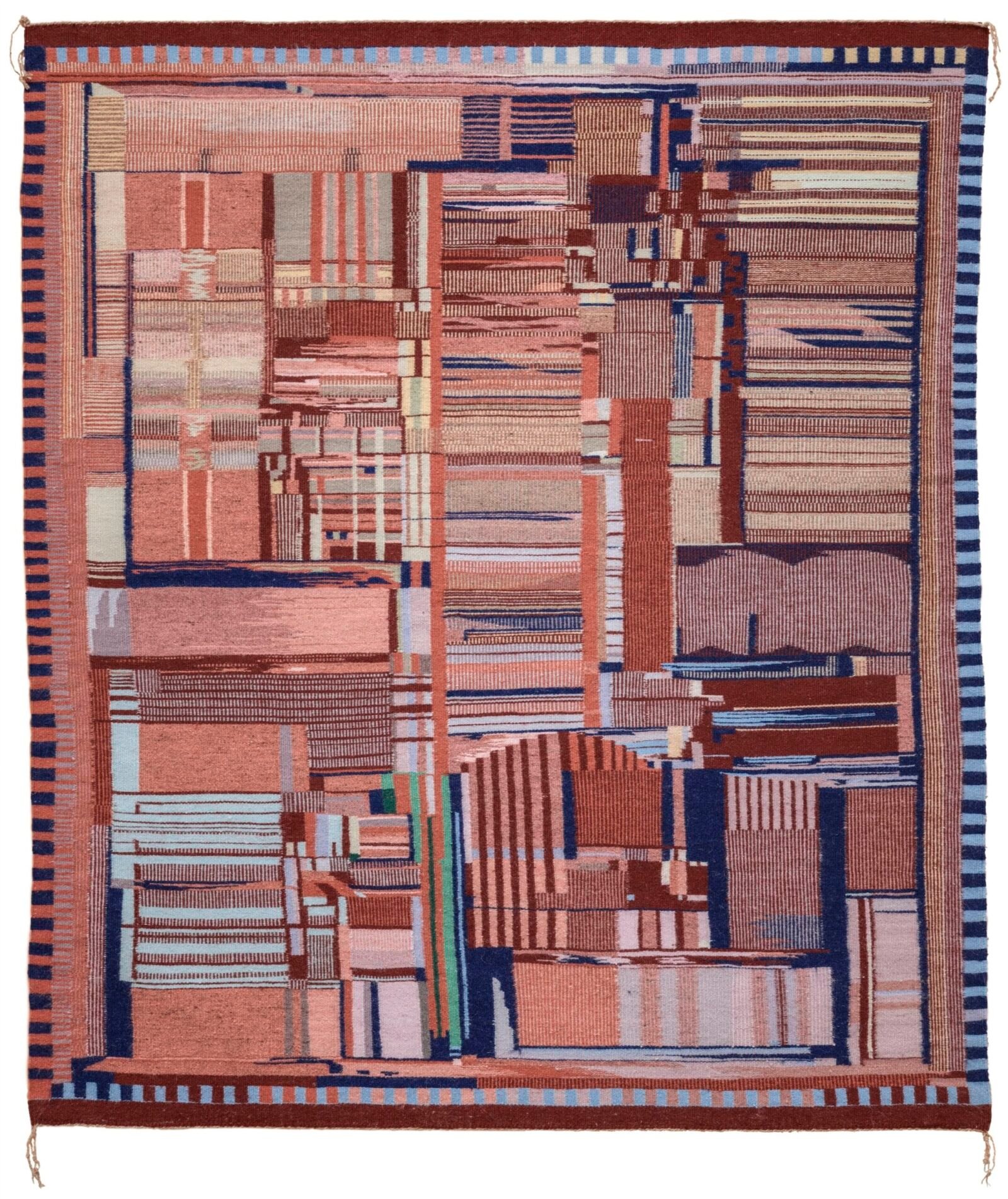

Schultz, a mathematician and teacher in addition to her studio practice, was commissioned by Intel in 1994 to create ‘Replica of a Chip’ as a gift to the American Indian Science & Engineering Societyan organization that is still active and focuses on advancing Indigenous people in STEM. As computer historian Ken Schirriff describes in detail blog post across the piece – especially its highly precise layout – the work highlights the seductive patterns of a groundbreaking piece of technology.

The first Pentium processor was released in 1993. The chip, the material on which the processor is made, is about the size of a fingernail and contains more than three million transistors. These microscopic switches control the flow of electricity to process data. Nowadays some contain powerful chips billions of transistors.

Schultz faithfully transferred the die pattern to a tapestry, using delicate loom techniques and working from a photograph of the chip. Unlike traditional Navajo textiles, the geometries in ‘Replica of a Chip’ are far from symmetrical.

She used yarn pigmented with vegetable dyes, and the cream-colored parts have the natural hue of Navajo-Churro wool. Schultz told Schirriff that the weaving process was slow and deliberate as she referred to the image, completing about two to one and a half inches per day. The painstaking and methodical process of directing warp through weft creates a beautiful tension between the immediate results we associate with digital tools today.

‘Replica of a Chip’ was the first in a series of fabrics that Schultz made from computer circuits, including one known as the Fairchild 9040. Although not as common as the Pentium, the Fairchild company is notable for its employment of Navajo workers at his Shiprock, New Mexico operation – within the Navajo Nation – in the 1960s and 1970s.

As part of a government initiative to try to improve economic living conditions on the reservation, Fairchild was encouraged to open a manufacturing center in Shiprock. “The project started in 1965 with 50 Navajo workers at the Shiprock Community Center producing transistors, and quickly grew to 366 Navajo workers,” Schirriff said. Ultimately, the company “employed 1,200 workers, and all but 24 were Navajo, making Fairchild the largest nongovernmental employer of American Indians in the country.”

In 1975, the Fairchild-Navajo partnership took a dramatic turn that marked its downfall. With the semiconductor industry at the time suffering from the crippling U.S. recession, Fairchild laid off 140 Navajo workers in Shiprock, which today still has a population of just over 8,000. The layoffs were a blow to the community. A group of twenty locals armed with guns responded by occupying the factory for a week.

While the episode ultimately ended peacefully, Fairchild decided to close down completely and move its operations abroad, further jeopardizing confidence in corporate interests on Navajo land.

The role of women in the production and assembly of electronics is often recognised. Schultz draws on ideas around gendered labor, visibility and the slippery concept of ‘progress’. Through the lens of Navajo history and craft, she discusses paradigm shifts in technology, economics, and social change through the language of fiber.

You can see ‘Replica of a chip’ in Woven Histories: Textiles and Modern Abstraction at the National Gallery of Canada in Ottawa, lasting until March 2, 2025.

Leave a Reply