RIDGEFIELD, Conn. — Martha Diamond: Deep time at the Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum, the first posthumous exhibition of work by the artist, who died in 2023, is a small overview of 27 years of extraordinary art. Born and raised in New York, Diamond earned a BA in art and art history from Carleton College in 1964, where she befriended artist Donna Dennis and art critic Peter Schjeldahl. After a period in Paris, the trio returned to New York and met the artists and poets of the second generation of the New York School, including Ron Padgett, Ted Berrigan and Joe Brainard. These associations and her location contributed to the DIY aesthetic of her work. In 1969, she moved to a loft on the Bowery, south of Houston Street, where she lived and worked for the rest of her life.

The exhibition, co-curated by Amy Smith-Stewart and Levi Prombaum, includes 30 works. I visited it last summer when it was at the Colby College Museum of Art (July 13 – October 23, 2024), and again when it traveled to the Aldrich Contemporary Museum. I left both shows thinking that by the time Diamond died she had become one of the best painters of her generation. This was never celebrated for many reasons, starting with the fact that she was a female painter at a time when painting was considered dead by critics and much of the art world.

A second reason is that she didn’t belong. She was neither a painterly realist, like the older members of the New York School, such as Fairfield Porter, Alex Katz, Neil Welliver, and Jane Freilicher, nor a member of the Neo. expressionist boys’ club, including Eric Fischl, David Salle and Julian Schnabel. Although some critics saw her as a neo-expressionist, the term never stuck because she was simply a better painter than the men, without the dramatic hoopla. Not one to make big claims, she let the paint do the heavy lifting.

The exhibition follows the arc of Diamond’s career from 1973 to 2000 and features paintings, drawings and monotypes, as well as ephemera presented in a vitrine. While the curatorial selection sharply maps her preoccupation with architectural structures from the late 1970s in paintings such as ‘Giant Yellow Hogan’ (1978), she got on the right track in the early 1980s, when she painted large wet-on-wet paintings started making. paintings of New York office and light manufacturing buildings from different eras. The clash of eras and architectural styles, facades and raking light and darkness, silent surfaces and turbulent skies, solid structures and melting light, became Diamond’s signature subject.

Diamond was in her late thirties when she began exhibiting her groundbreaking paintings. In an art world always looking for the next relevant thing, she became an ‘artist’, forever on the edge of something bigger but never achieving it. Perhaps this exhibition, along with its accompanying catalogue, is a sign that things are beginning to change and that her paintings will finally be seen and appreciated by a wider audience.

When I saw her paintings of buildings, I thought of the opening stanza of Frank O’ Hara’s love poem ‘Steps’:

How funny you are today New York

like Ginger Rogers in Swingtime

and St. Bridget's steeple leaning a little to the left

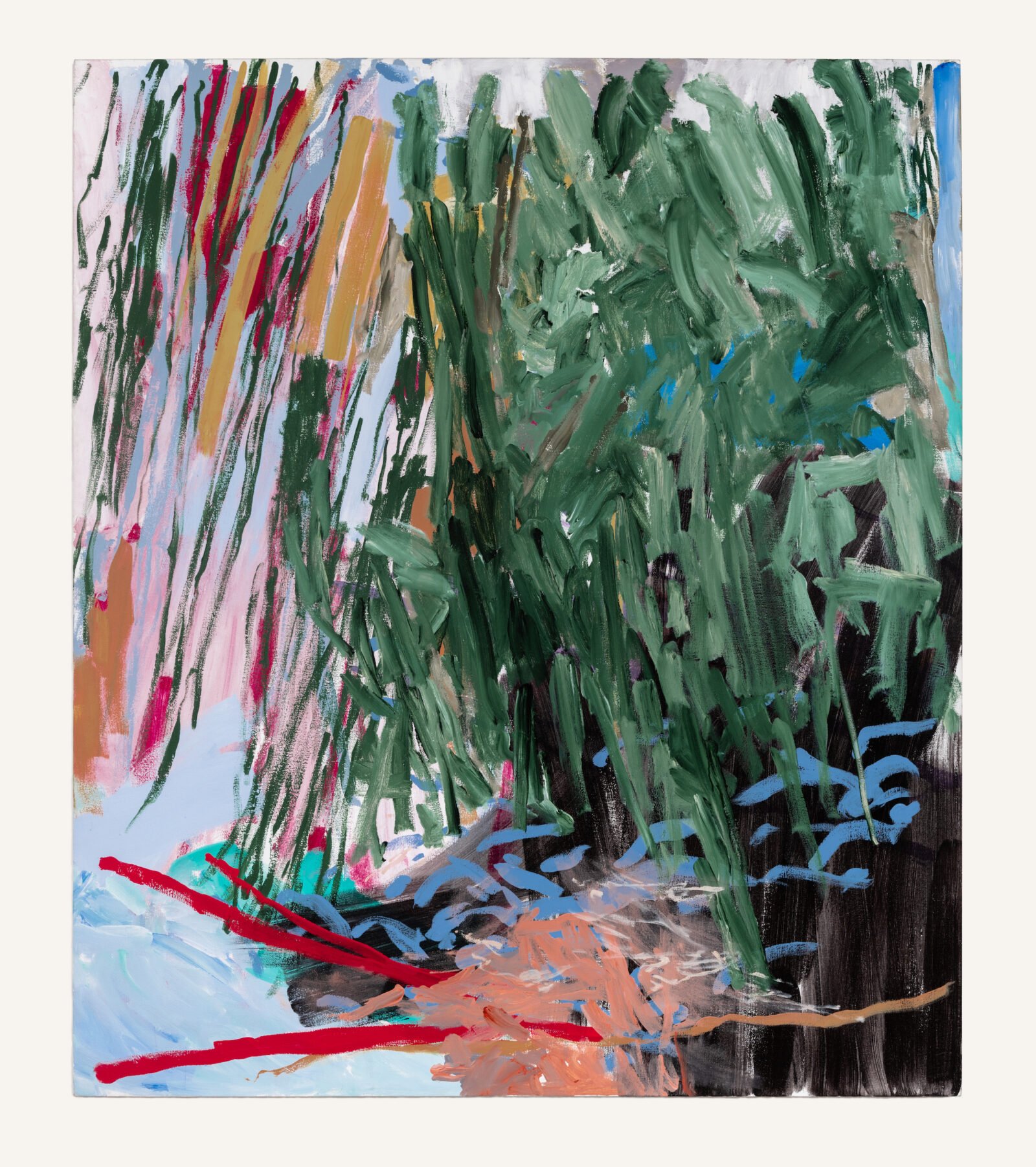

One of the fascinating things about Diamond’s paintings is the interplay between the paint and the subject, volume, surface, atmosphere and light. While many observers have written about the dance between abstraction and representation that plays out in her work, that assessment focuses on art historical categories, not the paint. She once said of her art, “When I express something, it’s how the brush works, not my emotion.”

Diamond’s attention to the brush’s ability to be simultaneously expressive and responsive is evident in her strongest paintings. In the thirty works on display we can see that she is becoming a master at this. It is clear that from the beginning she enjoyed working with a loaded brush and drawing with paint.

In “Cityscape with Blue Shadow” (1994), Diamond changes the viscosity of the paint from a streaky mix of gray and blue to solid yellow ocher, accentuated by short horizontal red stripes. Although the sky seems to be constantly changing, the building feels solid, but Diamond ignores this contradiction by adding another prominent element: blue vertical stripes form the shadow cast from an unknown source on the facade of the ocher building . It is in this dynamic that her skills are most evident. Diamond never filled in a shape. Everything is deliberate, the result of a touch that moves deftly from airy to light to direct pressure. What seems casual is anything but.

In “Change” (1981), vertical yellow brushstrokes pick up the underlayer of black without becoming muddy. The direction of the yellow and black lines articulates the volume and surface of the building. The carefully arranged blue intensities in “Center City” (1982) culminate in a moody, nighttime view of an unlit building. Paint is always paint, even when it becomes light, shadow, cloud-filled windows of a modernist building, solid surfaces or dissolving and melting shapes. While walking through Manhattan, Diamond sees the city rising around her, and admits it causes anxiety. Her paintings are full of joy and solitude, calmness and heightened consciousness.

Martha Diamond: Deep time continues at the Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum (258 Main Street, Ridgefield, Connecticut) through May 18. The exhibition was co-organized by the Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum and the Colby College Museum of Art, and co-curated by Aldrich’s Chief Curator, Amy Smith-Stewart, and Colby’s Katz Consulting curator, Levi Prombaum.

Leave a Reply