This article is part of a series aimed at under -represented traditional histories, investigated and written by the Craft Archive Fellows of 2024 and organized in collaboration with the Center for Craft.

The deceased Indian-American print maker Krishna Reddy was a daring artist and lifelong educator who extended his interest in sculpture into carving in a metal plate, so that the way we use color in printing today transform today. His philosophy as an artist and teacher was that the joy of creation should not be a lonely action. On the occasion of his 1981–82 retrospective In the Bronx Museum he explained his reasoning to an interviewer: “Once you have experienced it, why would you not see if someone else can use it?”

Reddy experimented deeply with materials and, based on a casual encounter, developed a new technique that simplified the process of printing different colors in Intaglio. The technique that he perfected – differently known as viscosity, mixed Color Intaglio or Intaglio simultaneous color prints – uses only one plate and lay colored inks of different viscosities with specialized roles to make a multi -colored image in just one pass through a press. Earlier, each color required its own etched plate; Creating a multi -colored image is a careful and difficult process to ensure that the layers of colors are correctly drawn up.

Reddy firmly believed that practicing artists made the best teachers, and he inspired others to experience the same satisfaction in the creative process. The Robert Blackburn printing workshopThe oldest and longest -running community print store in the United States was one of the first places that Reddy taught in New York City in New York City in 1968. There he continued to offer workshops and demonstration lessons for more than 30 years. Blackburn, a black American print maker, founded his workshop in 1947 and quickly established it as a cooperation channel for print makers from all over the world, especially color artists. Dozens of prints and sculptures from Reddy’s work can be seen in the New York print center in Krishna Reddy: Heaven in A WildflowerWalk through May 21. The organization will also offer public program and workshops in the spring to combine the dialog about Reddy with the Elizabeth Foundation for the Arts Robert Blackburn Printmaking workshop program, whose show Krishna Reddy and the printing workshopwhich I have put together will open on March 1. I collected oral history from various artists who studied with Reddy in Blackburn’s workshop to understand the pioneering spirit of his teachings of viscosity techniques, how he traverses the continuum of craftsmanship and art, and what it means, and what it means, and what it means , and what it means, and what it means to be a collaborative print maker.

Artistic development and Atelier 17

The early educational experiences of Krishna Reddy in India have formed his later artistic philosophies enormously. Born in Andhra Pradesh, India, in 1925, he was lucky to be able to go to the Rishi Valley School, founded by philosopher Jiddu Krishnamurti about the principles of research, self -consciousness and lifelong learning. Later, at the Art Academy of Visva-Bharati in Shantiniketan, a university founded by Poet and Nobel Prize receiver Rabindranath Tagore, Reddy investigated his interest in sculpture while promoting a connection with the natural world. In 1949 he traveled to Europe and studied sculpture with Henry Moore and then Ossip Zadkine, who recognized and suggested the graphic potential of Reddy that he worked with artist William Stanley Hayter in Atelier 17, a printing studio in Paris.

When Reddy came to Hayter’s Atelier 17 in 1951, it was already known as a place for artists such as Max Ernst, Alberto Giacometti and Joan Miro to experiment and work together. In the vast, open-layout space of the print studio, ideas flowed freely. Hayter was not interested in the commercial aspects of printing and encouraged artists to learn from each other and to collaborate with master printers at the studio.

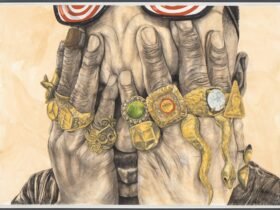

Reddy learned traditional black and white etching at Visva-Bharati, but at Atelier 17 he was able to experiment with applying color to his prints. Reddy worked on a metal plate because he would dig a sculpture and throw it out of the board with hand tools to cut deep reliefs that created images with dynamic movement and expression. A drop -spilled line oil created an opportunity for Reddy, together with colleague -Indian artist Kaiko Moti and Hayter, to experiment with applying colored inks in the most direct way. Reddy continued to print or viscosity of one plate throughout his life and became the best -known practitioner. He never left the joy of creating creating and offering artists a new way to think about color, texture and shape.

Krishna Reddy at Robert Blackburn printing workshop

Krishna Reddy and Robert Blackburn met in post -war Paris, a cultural hub for black artists and those from the former colonies of Europe. Both established and emerging artists freely mixed and shared ideas in the cafés of the city and each other’s studios. According to the catalog of the Bronx Museum Retrospective, Blackburn Poetic described the meeting in the spring of 1953 near the Pont des Arts: “It was a beautiful Parisian afternoon; There was this striking man in color whose soft vibrations pulled me to him. We spoke briefly. This meeting was to stay with me until our meeting ten years later in New York. “Blackburn was familiar with the experimental creativity of Hayter’s Atelier 17 from his time in New York, and it was in line with his own philosophy of not imposing aesthetic boundaries on artists.

During one of Reddy’s visits to New York in 1968, Blackburn invited him to teach in his print shop. In addition to their mutual respect, Reddy and Blackburn also shared similarities in their approaches to printing and education. They treated students as equals, while artists started their own journey of creativity and technical discovery. Blackburn cultivated a hospitable, imaginative environment that was famous for his spirit of openness and inclusion, who attracted various and international artists who took Reddy’s viscosity workshops – of whom many continued to work in viscosity during their career.

Artist and sculptor Michael Kelly Williams, who met Reddy for the first time as he took his lessons at Blackburn’s in the late 1970s, told me that he credits Reddy by promoting a feeling of cooperation and experiments in his own printing. For the print “West Indian Day Parade” (1983), Williams collaborated with fellow artist Helio Salcedo to draw the images on an abandoned plate with the help of engraving, metal stamps and texture effects. They experimented with the color scheme – where Salcedo applied the colors à la poupée And Williams using the viscosity technology – to create a lively and festive scene.

Artist Joyce Wellman was also interested in color and attended Reddy’s workshops next to Williams. The two often worked side by side in the open space of the print workshop and helped each other with the physical and difficult printing process. Wellman told me that Reddy taught her perseverance and encouraged her to think deeply about the record and the materials. His teachings went beyond the technical steps of printing, which extend to the philosophical aspects of creating a work of art.

Learning about Reddy in the 1970s via Indian newspaper clippings, the Indian artist Devraj Dakoji has registered in his workshop on color viscosity. He believes that nobody knew so much about making colors like red.

“Reddy was a genius when it came to color,” Dakoji told me in an interview. “He was able to combine colors to produce energy in his prints.” Initially he found viscosity complicated and technical and did not want to be busy with it – that is, until he learned Reddy’s process in New York. He also learned to collaborate with painters and sculptors, something that was missing in printing in India. Dakoji became a master printer at Blackburn’s, who produce viscosity prints such as “Evolution” (1995) and editioning for other artists, including the Indian artist MF Husain.

Kathy Caraccio was a monitor at the print shop and Reddy’s assistant for many of his viscosity workshops. “Many artists have followed that class – Bob Blackburn, AJ Smith, Otto Neals. It established a kind of viscosity harves at Blackburn’s, “she told me. Although Caraccio was technically never a Reddy student, she was influenced by her in her use of colors and radiant lines, as can be seen in early works such as “Universe” (1972).

Multiple legacies

Krishna Reddy has three continents and the converting of sculpture into Intaglio printing and left a network of legacies, from experiments in simultaneous color printing to creativity and inspiration for the artists he taught. Reddy probably believed that working artists made the best educators, and many of his students then ran viscosity at universities, community art spaces and print shops.

But even in his later years he never considered himself the teacher or expert, but a lifelong student. Marjana Pahor, a young student of him in the nineties, remembered her lessons with him. During an etching workshop in which Pahor worked on a composition that published city life, Reddy would encourage her to try different techniques to get the effect she wanted and then her questions to explain her creative process to him. She remembers that he told her: “You taught me something new today.”

Leave a Reply