Our planet’s Moon might look dead and stagnant from our vantage point here on Earth, but a new study suggests it was moving about just a ‘hot minute’ ago.

On the dark side of our neighboring satellite, astronomers have discovered a strange amount of geological activity that occurred as recently as 14 million years ago.

That might seem like a long time, but for the Moon, which is roughly 4.5 billion years old, that’s a snap of the fingers.

In its early days, the Moon’s surface, cobbled together from debris in Earth’s orbit, once hosted a hot magma ocean. Then, sometime around 3 billion years ago, the lunar surface began to cool.

From then on, volcanic activity on the Moon seems to have decreased significantly, and wrinkles of lava began to solidify on the surface, frozen in time for billions of years and occasionally altered by another collision.

“Many scientists believe that most of the moon’s geological movements happened two and a half, maybe three billion years ago,” explains geologist Jaclyn Clark from UMD.

“But we’re seeing that these tectonic landforms have been recently active in the last billion years and may still be active today. These small mare ridges seem to have formed within the last 200 million years or so, which is relatively recent considering the moon’s timescale.”

The idea that the Moon’s surface is still geologically active to this day is highly speculative and needs to be tested further, but there is reason to suggest the Moon was in motion more recently than scientists thought.

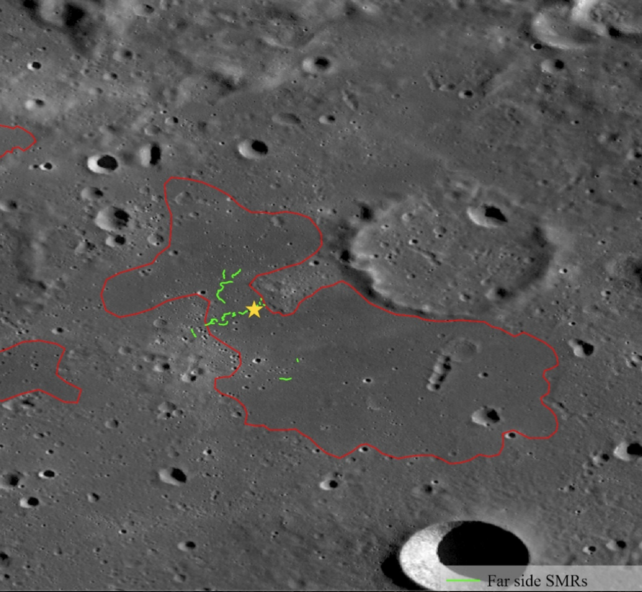

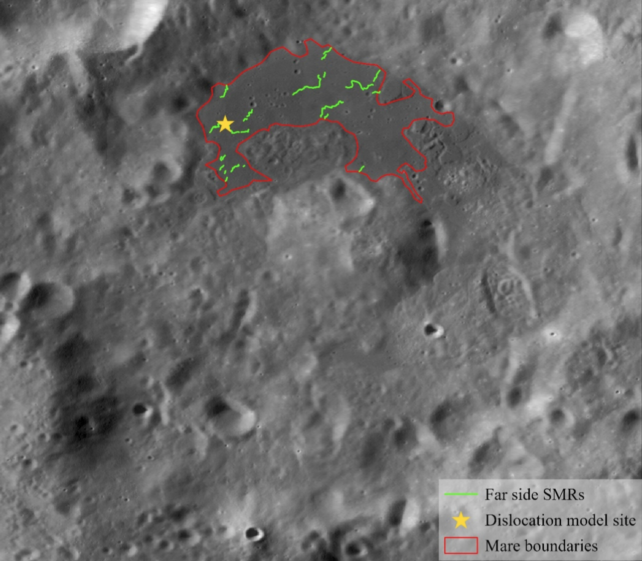

Researchers at UMD have used advanced mapping and modeling techniques to find 266 small ridges on the Moon’s far side that were previously undocumented.

The ridges discovered by Clark and her colleagues cluster around and cross-sect several lunar maria, which are dark splotches on the Moon’s surface, named after the Latin word for ‘seas’. From Earth, they do look like oceans, but they are actually vast plains of volcanic basalt.

Scientists think the maria were created when objects smashing into the Moon’s surface triggered extensive melting and an extrusion of lava filling ancient impact craters.

The far side of the Moon took more of these hits than the part we can see, but some evidence suggests it cooled off faster than the near side.

The new findings suggest that may not be true after all.

Most tellingly, some of these ridges have formed across very recent impact craters. The most recent of these was made just 14 million years ago.

“Essentially, the more craters a surface has, the older it is; the surface has more time to accumulate more craters,” Clark says.

“After counting the craters around these small ridges and seeing that some of the ridges cut through existing impact craters, we believe these landforms were tectonically active in the last 160 million years.”

Clark and her colleague’s estimates are based on imprecise calculations; however, the ages align well with younger, ridge-like features made from the Moon’s ongoing global contraction as it cools.

A study like this one is bound to inspire debate, but given that some wrinkles on the surface of the Moon suggest the satellite is still shrinking, it’s worth considering if the lunar surface is more malleable than it looks.

The study was published in The Planetary Science Journal.

Leave a Reply