:focal(1500x1014:1501x1015)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/20/4d/204d5d7f-972c-40d8-bda3-4e3b8a68a2e6/gettyimages-75509449.jpg)

Freddie Mercury of Queen, 1982 Tour at various locations in Oakland, California

Photo by Steve Jennings/WireImage via Getty Images

As midnight reached West London and Friday evening entered the first minutes of Saturday, November 23, 1991, the press officer for rock band Queen released a statement on behalf of frontman Freddie Mercury.

“Following the tremendous amount of suspicion in the press over the past two weeks,” Mercury said announced“I want to confirm that I have tested HIV positive and have AIDS.”

Even when he was isolated Garden lodgehis home in Kensington, he could see the cigarette smoke of paparazzi above his garden wall. “I felt it was right to keep this information private until now to protect the privacy of those around me,” he continued. “However, the time has now come when my friends and fans around the world will know the truth, and I hope everyone will join me, my doctors and everyone around the world in the fight against this terrible disease.”

Mercury concluded his letter with a final plea for privacy, a commodity that had proven elusive in recent years: “My privacy has always been very special to me, and I am known for my lack of interviews. Please understand that this policy will continue.”

His ill health had kept him out of the spotlight ever since last concert with Queen in 1986, and the Mercury and Queen press team publicly denied that he had HIV/AIDS even after his 1987 diagnosis. That it didn’t prevent British tabloids from hounding him about his sexuality and health: In 1990 for example Sun published a special story called ‘The Sad Face of Freddie Mercury’ with a photo of him leaving a doctor’s office ‘looking haggard and emaciated’.

After recording new music with his bandmates in Montreux, Switzerland, Mercury had returned to London for the final time. He languished in bed while doctors and visitors such as Elton John, his bandmates, former fiancée and long-time friend Mary Austinand his partner Jim Hutton kept him company during his shaky last days.

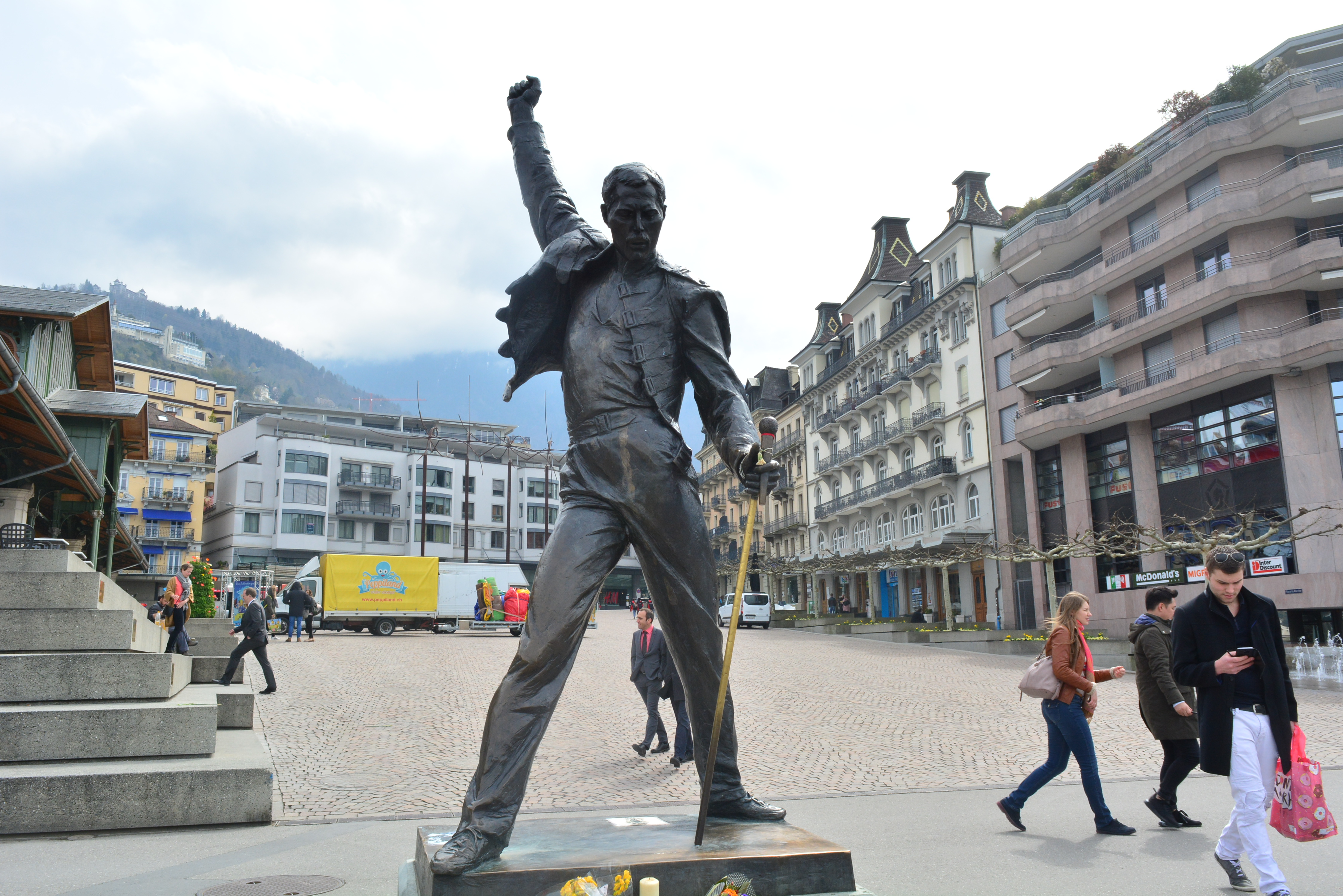

A statue of Freddie Mercury in Montreux, Switzerland. Queen recorded seven studio albums in Montreux, including Freddie Mercury’s final studio recording for Queen’s 1991 album “Innuendo”. Exploratorium efimeros via Wikimedia Commons under CC BY 4.0

On the day of his groundbreaking statement was released, Mercury’s condition was serious. “Freddie had by now lost his sight, could barely move his muscles, had given up all solids and was living on the bare minimum of fluids,” biographers Matt Richards and Mark Langthorne wrote in Someone to Love: The Life, Death, and Legacy of Freddie Mercury. “He drifted in and out of consciousness.”

It was clear that death was near. By releasing a statement, Mercury and his inner circle hoped to put an end to the aggressive media speculation that had plagued the singer as much as his illness – to provide relief in his final moments and to open up about the ongoing stigmatized illness.

He only lasted one day longer. Mercury was pronounced dead on November 24 at 6:48 pm. The official cause of death was bronchial pneumonia due to AIDS.

To write Rolling stonejournalist Jeffrey Ressner noted that Mercury – the man born Farrokh Bulsara from a Parsi Indian immigrant family Zanzibar– was the “first major rock star to die of AIDS.”

“We have lost the greatest and most beloved member of our family,” the band said later wrote in a statement. “We feel overwhelming sadness that he is gone, sadness that he must be cut down at the height of his creativity, but above all great pride in the courageous way he lived and died.”

Leave a Reply