In the morning, shimmering planes of light envelop the massive, interlocking forms of the cobalt blue glass of the Lippo Center in Hong Kong, which appear to expand and contract. On the other side of the world, the sun’s rays skim across the striped concrete facade of the Art and Architecture Building at Yale University, each facet of its Roman scale successively eclipsing another.

For Paul Rudolph, the architect of both buildings, a major design goal was a return to monumentality, a purposeful shift away from the ethereal soaring steel and glass structures that dominated mid-century America. Twenty-seven years after Rudolph’s death, the Metropolitan Museum of Art presents the first museum exhibition devoted to his life and work, organized largely around his famous presentation drawings, with supporting ephemera. His legacy is decidedly mixed; His works are endlessly litigated, both in public reception and often in court, with many threatened with demolition or redevelopment. But the strikingly monumental concrete buildings for which he is best known today represent a fraction of the output of this vanguard architect, whom Walter Gropius considered the star student among future greats Philip Johnson and IM Pei.

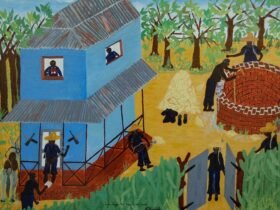

Rudolph’s remarkably prodigious production of drawings rewards close viewing: spaces are articulated through sharp crosshatching, changing densities of lines create volume. When color is used, it is used sparingly, often accentuating construction requirements or revisions. Although his drawing skills have long been celebrated, it is the clarity of his proposals that maintain their relevance.

In 1967, Rudolph accepted a commission from the Ford Foundation to create an alternative proposal to urban planner Robert Moses’ Lower Manhattan Expressway, often lightheartedly referred to as “LOMEX.” The resulting plan, depicted in four large drawings, was a vision in line with the development-oriented ethos of the time, which would have created thousands of housing units at the cost of radically changing the structure of the neighborhoods along the planned path. Instead of Moses’ city-traversing elevated 10-lane highway, Rudolph’s plan opted for a less disruptive, underground roadway, a “two-mile building” that connected the Holland Tunnel to the Williamsburg and Manhattan bridges with A- frame blocks of modular homes. built on top. The interchange, shown in ‘Perspective Drawing of the Lower Manhattan Expressway/City Corridor Project (Unbuilt), New York’ (1967-72), is a fantasy of urbanity, with extravagantly cantilevered monorail tracks stretching across the inescapable, if tastefully hidden , highway and surrounding junctions.

Fifty years later, the LOMEX proposal seems the height of mid-century hubris. Rudolph certainly built for the moment, but like all architects, he also hoped to build for history. In his drawings, people are usually depicted as futuristic swirls of dynamic, coiled lines. The city itself is often reduced to a wireframe mesh, softening the noise of urbanity for the master plan so carefully crafted. Of course, the surrounding environment would have been more than a static structure for the residents.

The world Paul Rudolph envisioned is best viewed at a glance: his ‘Rolling Dining Chair’ (1968) simplifies and complicates, reducing seating to planes of perspex attached to a tubular chrome frame, a design that merges light and space for an effortless feeling of airy contemporaneity. When Rudolph’s works are displayed as physical models, they can extend architectural understanding, sometimes too far for practical consideration. Perhaps this was an inherent flaw in his practice: his designs are best appreciated through the infinite plane of the drawing board. Rudolph’s unbuilt projects live on as unborn dreams, specters of progress that, even when confined to parchment, expand our vision.

Materialized space: the architecture of Paul Rudolph continues at the Metropolitan Museum of Art (1000 Fifth Avenue, Upper East Side, Manhattan) through March 16, 2025. The exhibition was organized by the Metropolitan Museum of Art in collaboration with the Library’s Paul Marvin Rudolph Archive of Congress.

Leave a Reply