“EVs do not have the power to drag our large caravan,” loudly explained the Lord to his female companion at the next café table.

He is right that today in Australia there are no pure electric vehicles (EVs) or plug-in hybrid vehicles (PHEVs) that are suitable for dragging a 3500 kg caravan.

This will change soon. A short glance at the best PHEV and Pure-Electric Sleep options that are now available, and on the way is followed by a brief explanation of the limitations of current battery technology.

Hundreds of new cars are available via Carexper now. Get the experts by your side and score a lot. Browse now.

Investing the issue of drag -friendly charging infrastructure is also important and will reveal how close to alternative powertrain technologies are to become viable drag options for Australian drivers.

We should then be able to guess which powertrain technology represents the best gambling for serious drag enthusiasts.

Phev

The newly released BYD Shark 6 PHEV has attracted a lot of attention for its value, usefulness, performance and decent EV-Alleen series. However, it is only assessed to drag 2500 kg, not the local benchmark of 3500 kg.

Even within his rated limits, the Shark 6 has shown that with its specific PHEV implementation there are some remarkable differences in tow options compared to a standard diesel or gasoline vehicle.

This is especially the case with dragging with a lower status of battery charge. However, some of the problems noticed are margins, so view the many Carexper Videos on the Shark 6 for details.

The soon released GWM Cannon Alpha is assessed to drag 3500 kg. In the event of release, it will also be closely investigated to see if it has similar problems.

In the meantime, the upcoming Ford Ranger PHEV, with his proven 3500 kg-papable ice carrier, should be free of SOC problems. However, the battery and the EV range range is very small and owners can save fewer dollars at the pump. In general, they are early days for these vehicles.

Dragging aside, they are a promising start, but the jury needs time to judge whether this set of PHEV UTES will become real sleep substitutes for traditional rivals.

EV

In our market, when it comes to dragging ‘serious’ loads, pure EVs have a towing problem: there are not!

Products from Rivian and Tesla can arrive here in the future, if they meet the Australian design rules, while the 4500 kg-compatible F-150-Liksem still has to be confirmed for release by Ford Australia, but is available in locally converted right-hand-drive form from Ausev and starts from $ 170k.

Later in 2025 the LDV Eeterron is 9. This promises 3500 kg towing power and up to 325 kW power. However, the 102kWh battery means that the already optimistic WLTP range of 430 km will never be threatened if it is close to the maximum assessment or less drags if the load also has poor aerodynamics.

The Riddara RD6, built by Geney, will probably also come here later in the year, but with a smaller battery than the LDV and the same 2500 kg towing limit as the Shark 6.

So, at the time of publishing, there are still no EVs who are able to drag a 3000 kg-plus caravan, and when the LDV becomes available here, the limited reach will still make a bad choice for heavy dragging far beyond urban areas.

If you really want a first -class EV for serious drags, you have to look at the US.

The current ‘Best in Class’ Pure EV is the Chevrolet Silverado EV. One of these 2024 models, with a 200 kWh battery, gets a formal EPA-rated range of 450 miles (720 km). With prices from US $ 70K for the extensive access versions that are supplied with almost 800 hp (588 kW) and more than 5500 kg drag, these are capable but expensive vehicles.

Although GM Specialty Vehicles brings in the Silverado for conversion of the right hand, the electric models are currently not available in Australia.

How far can they go? A Real-World comparison test with a 3000 kg of brick-shaped trailer has indicated the towing range of the EV at about half of the manufacturer’s EPA figure. You will be shocked how far a Chevy Silverado EV can drag versus a Ford F-1550 from petrol-driven!

The EV and a 3.5-liter V6 Benzine F-150 that dragged on the same roads at the same time identical trailers for 232 miles (373 km). Although the vehicles reached 75 mph (121 km/h) while dragging on the highway, part of the test was done at lower speeds on secondary roads.

This means that this was not only quickly ‘highway’ kilometers. The roads were also flat and the weather mild. These circumstances therefore represent close to a best-case scenario, because extreme weather and large hills increase energy consumption. The Silverado only indicated 15 miles of the remaining reach at the end of the test.

It was on average the equivalent of 38 mpg versus its rated 63MPG combined urban/highway figure. In the meantime, the gasoline F-150 almost exactly half (9.8 mpg) of its normal EPA combined efficiency of 20 mpg achieved, but due to the size of the 36-gallon (136l) fuel tank still had another 108 miles (173 km) until it was empty.

‘Tank’ size

The previous sentence is crucial. Although EV batteries are large, be heavy and pack a deadly tension, their current energy density is only a fraction of that of the diesel fuel that drives the most heavy UTES and 4WDs.

An EV with a 100 kWh battery that can weigh more than 500 kg contains only the same energy as 10 liters of diesel. A land cruiser or F-150 with 140 liters of fuel on board therefore has a huge 1400kWh of stored energy.

So even a huge EV, such as the 4000 kg Silverado above, with its huge 200kWh battery, still only wears the equivalent of 20 liters of fuel.

With that small ‘Tank’ of 20 liters, the incredible efficiency of electric motors means that it can manage 700 km before it has to be charged. However, if you drag something like a heavy caravan with ‘brick -like’ aerodynamics, especially at highway speeds, the enormous amount of energy needed to push all that air out of the way can halve more than the range, as shown above.

Charging infrastructure

The results of the Chevy EV are not bad at all, but there is another limiting factor that should consider the range: refuel. Although the test above revealed that the F-150 has chewed almost four times as much energy as the EV to drag the same distance, refueling the Ford is fast and easy.

It is easy, even with a large trailer, because almost every gas station enables the driver to drive, fill it without removing and driving away. Such an infrastructure is unusual in the EV -loading world. Australia is a typical case.

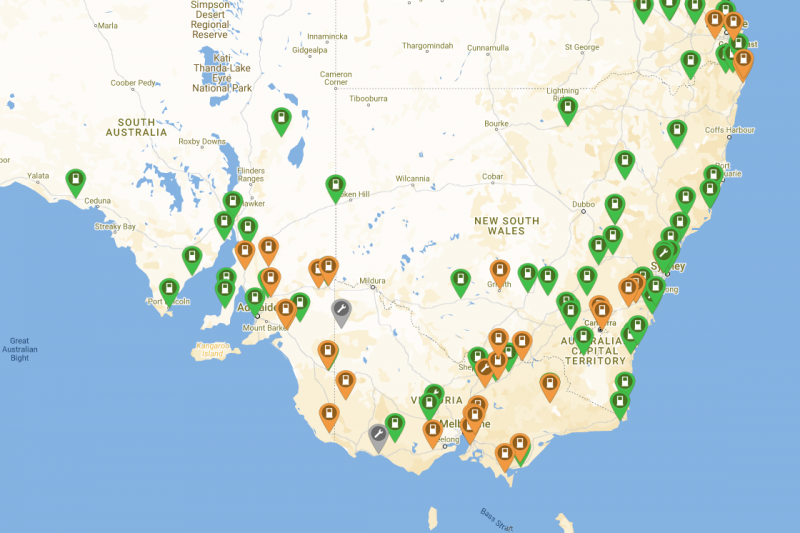

A quick glance at the ‘trail -friendly’ charging option on Plugshare shows the limited number of locations where EVs

Does not have to take it off during charging.

Plugshare is an essential app for EV owners: show where chargers are. Plugshare unveils only 20 such locations in the state of Queensland and 40 in NSW-with large parts of the state without drag-friendly charging stalls.

Throughout Australia there are only 142 charging stations throughout Australia (including 12 in Tasmania) where you can charge your EV without disconnecting your trailer. In comparison with more than 1000 powerful public charging locations Australia-wide from mid-2024.

This all means that dragging in Australia, especially in regional areas, is much easier with a combustion engine. It is a job that is most suitable for vehicles such as the Toyota Landcruiser, select variants of the Ford Ranger and other popular vehicles in that class.

It is not all bad news for electrified vehicles, because the charging infrastructure continues to grow at a healthy pace, so that future EV -automobilists are better supported.

Longer term also remains ahead of the battery technology, with a decrease in costs and an increase in energy density and loading speeds. In the heavy SUV and 4WD vehicle segments, however, this is unlikely that these are price -competing with combustion vehicles.

This is why Ford CEO Jim Farley is holding the production of new full-size electric SUVs and trucks. There are one

Medium -term solutions with which owners can enjoy some of the running costs, performance and emission benefits of electric driving, but can still drag a large boat or heavy caravan in Regional Australia?

A solution?

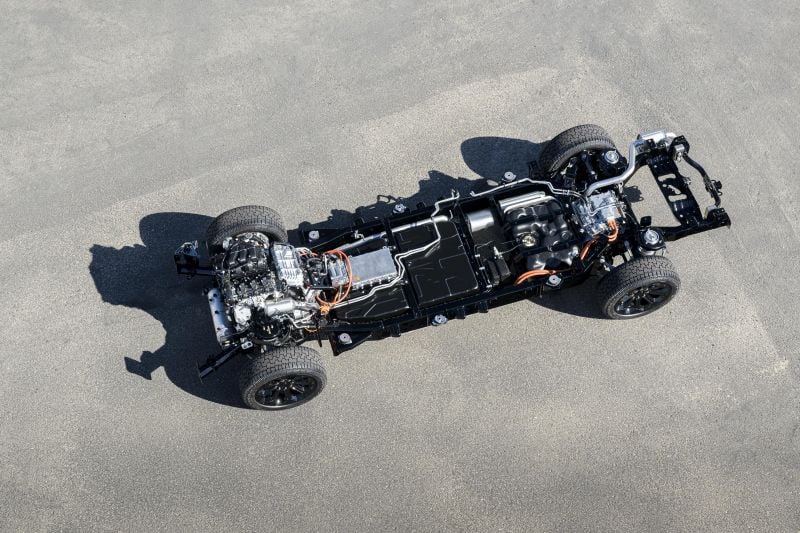

There can be a solution not far away. It is a PHEV truck in its actual size that has a number of similarities with Shark 6.

The RAM 1500 Ramcharger has two electric motors, which develops a total of 476 kW and powered by a large 92kWh battery. It can drag more than 6000 kg.

The battery can be charged externally DC and AC, but can also be charged by the 3.6-liter gasoline V6 incineration engine that works as a generator. The Ramcharger is on the North -American market later this year.

The combustion engine never drives the wheels: it simply generates electricity for the battery. In Pure EV mode, RAM truck rates the 3400 kg truck on just under 150 miles (241 km) of the range. The EV capacity would actually be larger, but a large part of the battery is hidden from use to maintain its nominal specifications and towing performance in serious conditions.

The key to the ability to drag heavy loads on long steep gradients is how RAM integrates the powerful combustion engine to work with the high -voltage components. The result is a vehicle that must offer all EV benefits of Instant Koppel that are available from 8 p.m. and quickly 4.7 seconds 0-100 km/h, but is still being assessed for 690 miles (1110 km) of the EPA range.

Even halving that range while dragging heavy loads would bring your parity with other heavy vehicles such as the gasoline-driven F-150. If you want to drag your heavy boat or caravan, you must have confidence with this vehicle to travel to remote places, knowing that you can fill yourself at regular service stations.

With that 6000 kg towing rating, this is an electrified vehicle that nobody claims ‘misses towing strength’. Let’s hope this RAM is reasonably priced and the pond jumps, because many Australians would like a vehicle with these options.

To summarize

So far, dragging has clearly been a problem for electric vehicles. In particular, battery energy density has limited the range of pure-electric vehicles and PHEVs.

Electric engines have the power to drag, with power and torque characteristics that are favorable in comparison with combustion engines, but drags heavy loads with poor aerodynamics, completes power reserves quickly.

The battery costs have fallen steadily, but the costs of the huge batteries that Pure EVs need for serious long-distance drag means that today is still the best value with diesel and gasoline vehicles. This is especially the case with dragging urban areas, because we have seen how limited drag-friendly EV charging infrastructure is at the moment.

The promising news is that there are several electrified vehicle options. These cleaner options save motorists on fuel money, offer functions and performance that is usually not seen from this class of vehicles and deliver considerable competition for your dollars.

Leave a Reply