:focal(319x237:320x238)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/6f/96/6f961f30-5ae7-436d-b5fd-f32902f6b33e/the_marie_antoinette_watch_displayed_at_22versailles-_science_2.jpeg)

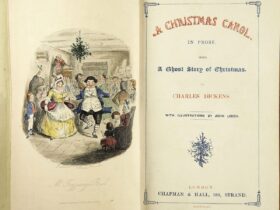

A visitor examines a watch made by Abraham-Louis Breguet for Marie Antoinette.

Science Museum Group

The extensive grounds of the lush French gardens Palace of Versailles are not only a masterpiece of landscape architecture, but also a sign of 17th century technical innovation. For example, the property’s ornamental fountains and ponds were only made possible by a purpose-built home machine who drew water from the Seine and pushed it up a steep hill to Versailles.

The machine was designed at the request of the French king Louis XIV– the monarch who ordered Versailles, also known as the Sun King. His and his successors’ courts are mainly remembered for their ostentatious finery, but their immense wealth also made discoveries possible, and Versailles turned into a hotbed for science: a theme explored by a new exhibition at the Science Museum in London: “Versailles: science and splendor.”

“The exhibition highlights how science flourished at Versailles, from the kings’ personal interest in luxurious scientific instruments and spectacular demonstrations, to its strategic role outside the palace through newly established institutions and scientific expeditions,” said Glyn Morgan, curator of the museum for exhibitions. , in one statement.

Jean-Dominique Cassini’s map of the moon Observatoire de Paris/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/ee/c5/eec56cdc-d40a-4ffe-bca6-a0aecbec34c5/jean-dominique_cassinis_map_of_the_moon__observatoire_de_paris_2.jpeg)

The show spans the 17th and 18th centuries and covers the reign of Louis XIV (who founded the French government). Academy of Sciences in 1666), Louis XV And Louis XVI (who was executed in 1793 during the French Revolution). Using more than 120 artifacts, the exhibition illustrates the importance of art and science at the French royal court.

Many of the objects demonstrate innovations in medicine, such as a curved scalpel designed by Louis XIV’s royal surgeon, Charles-François Felix. When the king developed a royal anal fistula, his surgeon had to invent a custom-made scalpel. Félix tested his tools on local farmers, killing several. Like the GuardianJonathan Jones writes: “The rehearsals worked: he repaired the royal fistula and Louis XIV lived on until 1715, his 72-year reign a world record.”

Under the reign of Louis XV (who ruled between 1715 and 1774), a midwife called Madame du Coudray became a powerful force against French infant mortality. The king hired her to travel through rural France to train other midwives in the mechanics of birth, using “sophisticated life-size mannequins,” the statement said. Du Coudray ultimately trained more than 5,000 women and doctors, and her last surviving model is on display in the exhibition.

Part of a mannequin used by Madame du Coudray to train midwives Musée Flaubert d’Histoire de la Médecine / Métropole Rouen Normandie/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/6b/8a/6b8aedaa-070c-4efb-b459-57471d7418d7/part_of_the_mannequin_of_madame_du_coudray___musee_flaubert_et_dhistoire_de_la_medecine_1.jpeg)

After Louis XV died of smallpox, his son and successor Louis XVI announced that the royal family would be vaccinated. The exhibition includes posters created to reassure the public about the success of the strategy.

Science at Versailles expanded to include the wonders of the natural world. French botanists grew and studied exotic plants. Versailles had one menagerie filled with animals like coatis And cassowaries. Visitors to the Science Museum can see the menagerie’s most famous resident: Louis XV’s rhinoceros, given to the king by a French governor based in India and later dissected and taxidermy after his death.

“When it was studied by scientists, it became incredibly important to our growing zoological knowledge,” says Morgan Observerby Vanessa Thorpe. “The photos really didn’t do justice to how impressive and full of character it is. The skin is almost jet black.”

Louis XV’s rhinoceros was dissected and taxidermied after his death in 1793. Science Museum Group/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/f3/33/f3331a3a-6e19-4f13-85b2-df414fae6819/versailles-_science_and_splendour_science_musuem_london_2024_1.jpeg)

His philosopher can also be seen Emilie du Châtelet‘s handwritten, annotated French translation of Isaac Newton Principia Mathematica; the watch made for Louis XVI’s wife, Marie Antoinette, by Abraham-Louis Breguet; and an early one map of the moon drawn by Jean-Dominique Cassini in 1679. The French Revolution claimed the lives of some thinkers from the French royal court, but their progress was lasting. According to the Guardian“Science progressed.”

“Royal ambition, scientific knowledge and ideals of beauty culminated at Versailles in spectacular displays and brilliant innovations from the brightest minds of the time,” Ian Blatchford, director and chief executive of the Science Museum Group, said in the statement. “We are excited to introduce our visitors to these fascinating stories through the beautiful exhibits.”

“Versailles: science and splendor‘ can be seen at the Science Museum in London until April 21, 2025.

Leave a Reply