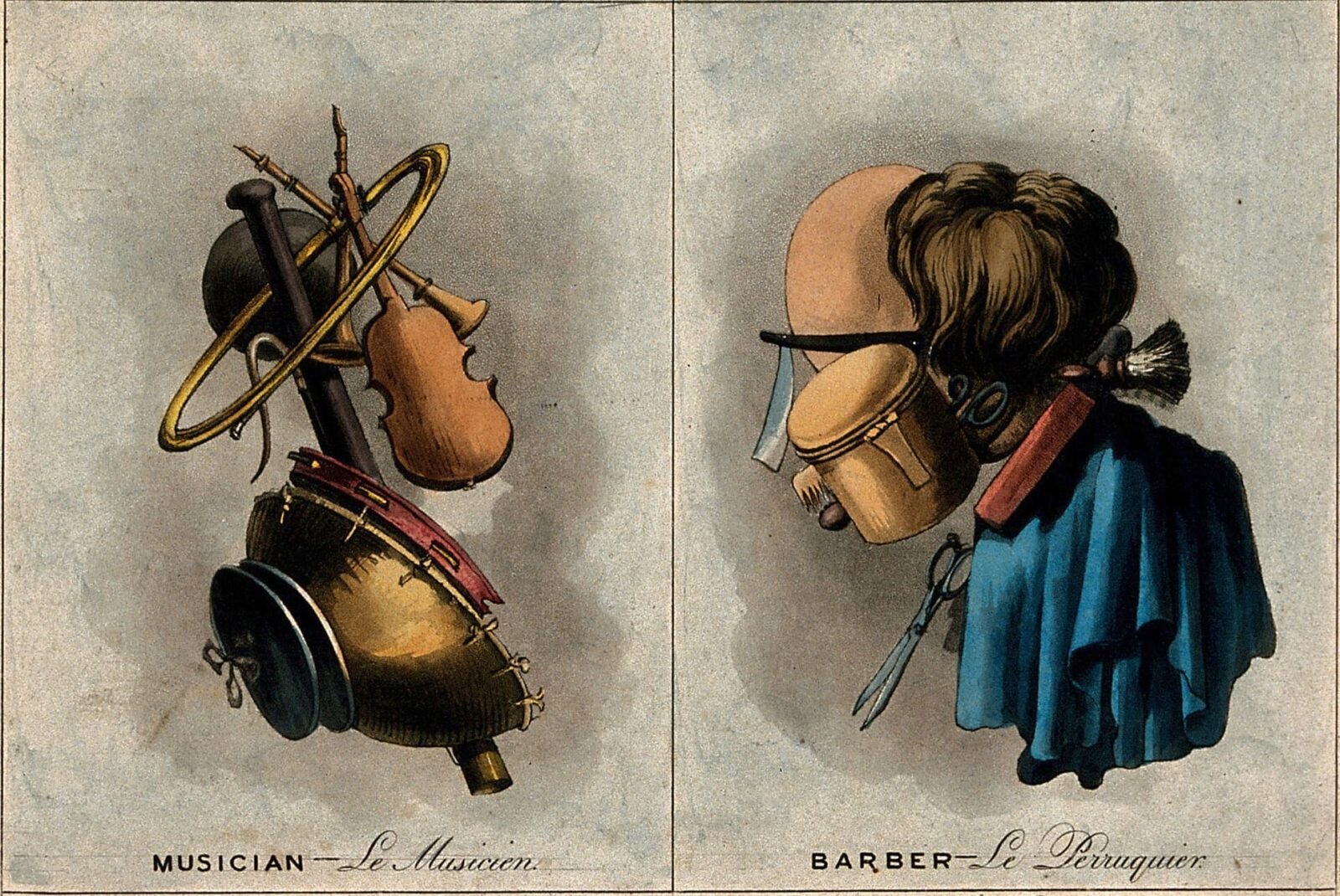

In the 16th century, Italian Renaissance painter Giuseppe Arcimboldo stimulated an idiosyncratic trend in portrait art, in which the symbolism of fruits, animals and objects was elaborated by arranging them compositionally in human faces.

Arcimboldo’s work inspired some European illustrators to depict merchants as physical performances of their work, such as Nicholas de Larmessin in the 17th century and Martin Engelbrecht on the 18th. They literally became the instruments of the subjects’ professions.

Published around 1800, based in London Samuel William Fores continued the playful – if sometimes disturbing – tradition of composite portraits in a series of aquatints depicting a florist, a baker, a gunmaker, a tailor and several others, made from the sum of their tools and wares. For example, a blacksmith consists of an anvil, a bellows and a hammer, while a fruiter – a greengrocer – is made of produce and baskets.

The Public Domain Review points out the meaning of the title of the series, Hieroglyphics: “If the print indeed dates from around 1800, then it would be the image shortly after the discovery in 1799 of the Rosetta Stone by Napoleon’s troops during their invasion of [Egypt]– and this at a time when the idea of hieroglyphics was still very much in the air.”

We currently understand that the word “hieroglyphics” denotes an ancient writing system in which images replaced text, so the title may take some license on that interpretation. But that may also be beside the point. If The Public Domain Review continues: “…it is as if the substitution itself is sufficient, whether it is a word or a strip of face, it does not matter – the whole world is seen as representable in a landscape of objects.”

Print from Hieroglyphics are currently held in the Welcome collection in London, where you can explore the library and exhibitions for free.

Leave a Reply